Explaining The Neglect of Doug Engelbart's Vision: The Economic Irrelevance of Human Intelligence Augmentation

Doug Engelbart’s work was driven by his vision of “augmenting the human intellect”:

By “augmenting human intellect” we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems.

Alan Kay summarised the most common argument as to why Engelbart’s vision never came to fruition1:

Engelbart, for better or for worse, was trying to make a violin…most people don’t want to learn the violin.

This explanation makes sense within the market for mass computing. Engelbart was dismissive about the need for computing systems to be easy-to-use. And ease-of-use is everything in the mass market. Most people do not want to improve their skills at executing a task. They want to minimise the skill required to execute a task. The average photographer would rather buy an easy-to-use camera than teach himself how to use a professional camera. And there’s nothing wrong with this trend.

But why would this argument hold for professional computing? Surely a professional barista would be incentivised to become an expert even if it meant having to master a difficult skill and operate a complex coffee machine? Engelbart’s dismissal of the need for computing systems to be easy-to-use was not irrational. As Stanislav Datskovskiy argues, Engelbart’s primary concern was that the computing system should reward learning. And Engelbart knew that systems that were easy to use the first time around did not reward learning in the long run. There is no meaningful way in which anyone can be an expert user of most easy-to-use mass computing systems. And surely professional users need to be experts within their domain?

The somewhat surprising answer is: No, they do not. From an economic perspective, it is not worthwhile to maximise the skill of the human user of the system. What matters and needs to be optimised is total system performance. In the era of the ‘control revolution’, optimising total system performance involves making the machine smarter and the human operator dumber. Choosing to make your computing systems smarter and your employees dumber also helps keep costs down. Low-skilled employees are a lot easier to replace than highly skilled employees.

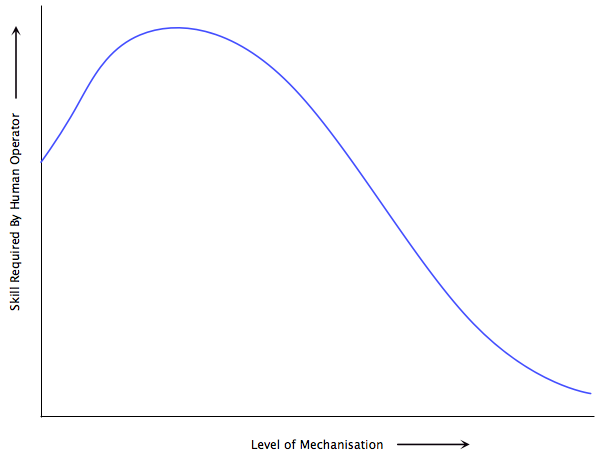

The increasing automation of the manufacturing sector has led to the progressive deskilling of the human workforce. For example, below is a simplified version of the empirical relationship between mechanisation and human skill that James Bright documented in 1958 (via Harry Braverman’s ‘Labor and Monopoly Capital’). However, although human performance has suffered, total system performance has improved dramatically and the cost of running the modern automated system is much lower than the preceding artisanal system.

AUTOMATION AND DESKILLING OF THE HUMAN OPERATOR

Since the advent of the assembly line, the skill level required by manufacturing workers has reduced. And in the era of increasingly autonomous algorithmic systems, the same is true of “information workers”. For example, since my time working within the derivatives trading businesses of investment banks, banks have made a significant effort to reduce the amount of skill and know-how required to price and trade financial derivatives. Trading systems have been progressively modified so that as much knowledge as possible is embedded within the software.

Engelbart’s vision runs counter to the overwhelming trend of the modern era. Moreover, as Thierry Bardini argues in his fascinating book, Engelbart’s vision was also neglected within his own field which was much more focused on ‘artificial intelligence’ rather than ‘intelligence augmentation’. The best description of the ‘artificial intelligence’ program that eventually won the day was given by J.C.R. Licklider in his remarkably prescient paper ‘Man-Computer Symbiosis’ (emphasis mine):

As a concept, man-computer symbiosis is different in an important way from what North has called “mechanically extended man.” In the man-machine systems of the past, the human operator supplied the initiative, the direction, the integration, and the criterion. The mechanical parts of the systems were mere extensions, first of the human arm, then of the human eye….

In one sense of course, any man-made system is intended to help man….If we focus upon the human operator within the system, however, we see that, in some areas of technology, a fantastic change has taken place during the last few years. “Mechanical extension” has given way to replacement of men, to automation, and the men who remain are there more to help than to be helped. In some instances, particularly in large computer-centered information and control systems, the human operators are responsible mainly for functions that it proved infeasible to automate…They are “semi-automatic” systems, systems that started out to be fully automatic but fell short of the goal.

Licklider also correctly predicted that the interim period before full automation would be long and that for the foreseeable future, man and computer would have to work together in “intimate association”. And herein lies the downside of the neglect of Engelbart’s program. Although computers do most tasks, we still need skilled humans to monitor them and take care of unusual scenarios which cannot be fully automated. And humans are uniquely unsuited to a role where they exercise minimal discretion and skill most of the time but nevertheless need to display heroic prowess when things go awry. As I noted in an earlier essay, “the ability of the automated system to deal with most scenarios on ‘auto-pilot’ results in a deskilled human operator whose skill level never rises above that of a novice and who is ill-equipped to cope with the rare but inevitable instances when the system fails”.

In other words, ‘people make poor monitors for computers’. I have illustrated this principle in the context of airplane pilots and derivatives traders but Atul Varma finds an equally relevant example in the ‘near fully-automated’ coffee machine which is “comparatively easy to use, and makes fine drinks at the push of a button—until something goes wrong in the opaque innards of the machine”. Thierry Bardini quips that arguments against Engelbart’s vision always boiled down to the same objection - let the machine do the work! But in a world where machines do most of the work, how do humans become skilled enough so that they can take over during the inevitable emergency when the machine breaks down?

- via Thierry Bardini’s book ‘Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing

‘ ↩

Comments

Brett

That might simply be impossible, just like how most people in the US can't just take up agriculture if we had to. You just need to build enough redundancy into the system so that a failure in one particular aspect of it doesn't completely derail the whole economy. And I suspect we'll keep around a number of skilled technicians trained to deal with this. It's like how most people are just "dumb operators" of their cars, and take them to a mechanic when they break down in a way that requires more than the simplest repairs.Ashwin

Brett - the scenario that I'm referring to is not that where you need to take the car to the mechanic, but one where the self-driving car develops a fault in the middle of the road and you need to take control of it. This was the sort of scenario that happened with the AF447 crash which I discuss here https://www.macroresilience.com/2011/12/29/people-make-poor-monitors-for-computers/ .

Brett

But that just comes back to my point about redundancy. If the main auto-driving system has a failure in the middle of the road, you build in a back-up system that turns on the hazard lights and pulls the car to a stop, even if it's in the middle of the road. Or you have another system take remote control of the car and steer it to the side, which isn't unthinkable considering some of the experiments being done with monitoring cars and traffic. Granted, that's going to be more complex in some areas than with others (like with planes where the auto-pilot fails), but it's not impossible.

Brett

To add- I did read the part about the "fallacy of defense in depth". But if you vastly reduce the possibility of an error happening because it relies on multiple back-up systems failing, that still counts as a success. You ultimately can't protect against all failure, just greatly reduce it.

Ashwin

Brett - it only counts as a success if the magnitude of the failure event doesn't escalate accordingly. A lot of the research on the 'fallacy of defense in depth' has been done in domains like airplanes and nuclear plants where the buildup of latent errors can cause a catastrophic failure. Same applies in finance. So it depends upon the domain and the particular case.

Ashwin

On the auto-driving system, you're basically arguing for a fully automated system that takes into account every possible scenario. Till we can achieve that (and we haven't yet), the problem exists.

Gene Golovchinsky

I think one problem with Engelbart's argument is the confusion between interface complexity and task complexity. I would argue that the more complex, cognitively demanding the *task* is (running a power plant, landing an airplane, etc.) the more the *interface* has to stay out of the way. One can tolerate interface idiosyncrasies in MS Word much more than in an airplane because the tasks are less demanding and the consequences of malfunction are less severe. This does not argue against the need for skilled operators nor against the need for competent interface design. Appropriate interface design is orthogonal to the complexity of the task, to the sophistication of the user, or to the need to foster learning. While differences in task and operator skill call for differences in interfaces, it does not follow that interfaces should be difficult to use once the user's skills and task are taken into consideration.

Ashwin

Gene - That's an excellent point. Thanks.