The Case For Allowing Banks to Fail

In many previous posts on this blog, I outlined why allowing the incumbent banks to fail when they become insolvent is a pre-requisite for achieving macroeconomic resilience. In my previous post I outlined how allowing such failure can be managed without causing a deflationary economic collapse in the process. Nevertheless, there are many who believe that a no-bailouts policy is tantamount to ‘financial romanticism’. In criticising the no-bailouts approach, Krugman deploys three arguments:

Policy makers will intervene anyway

It is undeniably true that policy makers will almost certainly move to stabilise the banking sector in times of economic distress. The aim of my ‘program’ was simply to sketch out a possible alternative that could be deployed rapidly during a crisis. Although I have some sympathy for policy makers asked to stabilise the economy during the largest financial crisis since the Great Depression, it is worth noting that the same policy of implicit and explicit support has been extended to failing banks at almost every point since WW2 - even in many instances when the fallout would have been much smaller. It is this prolonged stabilisation that has left us with such a fragile financial system.

Are guarantees and safety net plus regulation the only feasible strategy?

I have no disagreement with the argument that “ bank regulation is important even in the absence of bailouts”. There are many industries which are regulated simply for the purposes of protecting their customers and banking is no different. However I disagree strongly with the notion that regulation can prevent the abuse of these guarantees. The history of banking is one of repeated circumvention of regulations by banks, a process that has only accelerated with the increased completeness of markets. Just because deregulation may have accelerated the extraction of the moral hazard subsidy (which it almost certainly did) does not imply that re-regulation can solve the problem. Banks now have at their disposal the ability to engineer synthetic exposures tailored to maximise rent extraction - the ‘synthetic CDO super-senior tranche’ that was at the heart of the losses in the investment banks in 2008 was one such invention. It is the completeness of this menu of options that banks possess to game regulations that distinguishes banking from other regulated industries. Minsky was well aware of the impact of financial innovation on the resilience of the financial system which is why he understood that the so-called golden age of the 50s and the 60s was “an accident of history, which was due to the financial residue of World War 2 following fast upon a great depression”.

Maturity Transformation and the Diamond-Dybvig framework

The core rationale of the Diamond-Dybvig framework is that banks are susceptible to self-fulfilling runs due to their unstable balance sheet comprising of long-maturity illiquid assets and on-demand liquid liabilities i.e. deposits. The implicit rationale is that maturity transformation has a beneficial impact. As William Dudley explains it, “the need for maturity transformation arises from the fact that the preferred habitat of borrowers tends toward longer-term maturities used to finance long-lived assets such as a house or a manufacturing plant, compared with the preferred habitat of investors, who generally have a preference to be able to access their funds quickly. Financial intermediaries act to span these preferences, earning profits by engaging in maturity transformation—borrowing shorter-term in order to finance longer-term lending”.

But what if there is no maturity mismatch for banks to intermediate? In a previous post I have argued that “structural changes in the economy have drastically reduced and even possibly eliminated the need for society to promote and subsidise maturity transformation.” The primary change in this regard is the increasing assets invested in pension funds and life insurers. Through these vehicles, households provide capital that strongly prefers long-maturity investments that match its long-tenor liabilities.

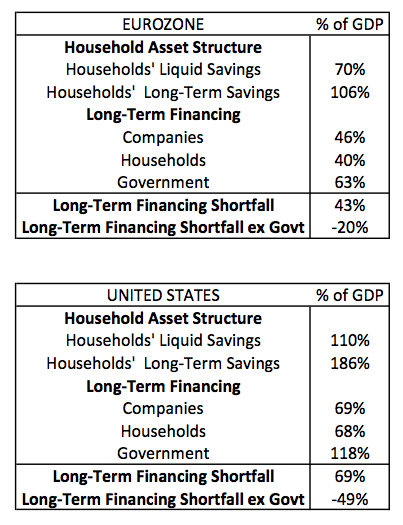

But how significant is this phenomenon and what does it mean for the economy-wide mismatch? In a recent research report, Patrick Artus at Natixis dug out the relevant numbers which I have summarised below:

In both the United States and Europe, household long-term savings (which includes pensions) is more than sufficient to meet the long-term borrowing needs of both the corporate and the household sector. In the case of the United States which issues its own currency, the need for maturity transformation can simply be eliminated by adjusting the government debt maturity profile accordingly. It is worth noting that even a significant proportion of the government debt in the above table is of a fairly short maturity.

The expansion that ended in 2008 was characterised by an expansion in the volume of long-term credit investments, but as Lord Adair Turner observed, in the United Kingdom “only a small proportion of those ended up in the balance sheets of long term hold-to-maturity investors such as pension funds or insurance companies. Instead the majority of UK residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) in particular were held by investing institutions, such as SIVs and mutual funds, behind which stood – at the end of the chain – short-term investors.” As Minsky might have predicted, maturity transformation was simply a tool to enter into a levered carry trade at the taxpayers’ expense.

In a world where maturity transformation does not even improve the efficiency of the economic system, Diamond-Dybvig and much of the rationale for our current banking and monetary system simply do not hold. The implications of this are not that we must ban maturity transformation. As Rajiv Sethi points out, even non-banking firms engage in maturity transformation and any attempt to stamp it out is futile. However, it is crucial that firms (banks or otherwise) that engage in maturity transformation are allowed to fail when they run into trouble.

Comments

JKH

“In the case of the United States which issues its own currency, the need for maturity transformation can simply be eliminated by adjusting the government debt maturity profile accordingly.” Yes, but you can eliminate it only by changing the institutional framework as well. E.g. if the government stops issuing bonds altogether, a government bank could issue deposits corresponding to deficits. That would probably satisfy all the demand for short term liquid deposits and provide a pretty direct way of insuring them as well. Existing commercial and investment banks and others would be forced to issue maturity matching liabilities for their assets. It’s also in essence a form of 100 per cent reserve system. Otherwise, commercial banks have no practical way of fully matching the maturity of the short term deposits they issue now. It is not the intention to mismatch so much as the demand for short term deposits from the public and the lack of natural supply of short term loans on the other side. It is a structurally forced mismatch. And even though pension funds tend to have the reverse mismatch problem to banks, there is no way of combining the risk in aggregate in such a way to solve the problem of effectively matching very short term bank deposits under the existing institutional framework. Finally, you should distinguish between commercial bank and investment banking functions as they relate to mismatches. Commercial banking mismatches in liquidity are to a great degree non-discretionary. Again, that’s because the banking public demands short duration deposits as liquidity and money, and you’re never going to have a natural source of short duration assets to match. On the other hand, investment bank functions are mostly discretionary when it comes to mismatching because they require wholesale funding choices as opposed to comparatively passive retail deposit gathering.

FT Alphaville » Further reading

[...] The maturity mismatch case for winding up [...]

Ashwin

JKH - Thanks for the comment. So yes, to the extent that there is demand for short-term liquid deposits, I'd rather the govt issue T-bills to back deposits or even deposits directly. I am leaving the option to issue bonds open because depending on the ALM demand from pension funds etc, it may still be worthwhile to issue bonds. For example, the UK has a much longer average maturity of debt outstanding than the US primarily because its ALM rules on liability-matching generate a much greater demand on the long-end. I'm still not convinced that we need to force matching or move to a narrow banking system for two reasons: One, the ability of the economy as a whole to get around these rules but especially the banks. In this speech http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/speeches/2010/speech455.pdf Mervyn King made the point that macro-mismatch can go up without micro-mismatch being detectable by regulators i.e. micro-prudential regs + gaming results in macro-fragility. Two, we're taking away the point of elasticity of money supply from the banking system to the govt. So way I understand it, banks cannot create horizontal money ex nihilo anymore. But I could be mistaken on this - there may be some way to preserve this capacity. I still tend to lean to the Schumpeterian view that this elasticity to fund new projects is important, but it's also possible that the long-term funds coming from PFs, insurers etc make this ability redundant.

Ashwin

And JKH - your comment on commercial banks not really having a choice in many instances is correct. I'd only add that the evolution of the shadow banking sector was primarily aimed at maximising the economy-wide credit carry trade and the rents from that.

charles

"As Rajiv Sethi points out, even non-banking firms engage in maturity transformation and any attempt to stamp it out is futile. " I think this is wrong : maturity transformation could be restricted to firms with low leverage (say a liabilities to equity ratio of 2 or 3). That will leave most non-banking firms out, and the non-banking firms which would remain would be quite likely to be doing some kind of financing activity Additionally, maturity tranformation should be automatically associated with stringent mark-to-market of financed assets. The dualities MTM/transformed funding vs Held-to-maturity/matched funding are fundamental. Of course, bankers don't want to hear about it because they are all in the Held-to-maturity/transformed funding game, essentially avoiding to pay the Central Bank (and therefore the Sovereign) the liquidity premium they should pay.

Ashwin

Charles - my point is simply that trying to enforce such a rule is incredibly difficult in practise. You can hide leverage off the balance sheet, you can layer leverage across subsidiaries etc. On the MtM issue, I completely agree. The more that is marked to market the better. I wrote a post on this topic a while ago https://www.macroresilience.com/2010/02/07/mark-to-market-accounting-and-the-financial-crisis/

Anders

Ashwin - I think you may draw the wrong conclusion when you compare household assets and companies' liabilities. A perusal of the UK's sector financial balances suggests that in fact the corporate sector is running insufficiently large financial deficits. If businesses invested more, this would help households to run their desired surpluses whilst allowing the budget deficit to fall. (This shouldn't even be controversial, although the steps to be taken to cause this situation to occur are clearly not obvious.) If this were to happen, business' long term financing needs would grow, certainly exceeding households' desired long-term savings. UK households currently hold 83% of GDP in currency and deposits. Doesn't this alone make some maturity transformation inevitable, unless you want to look into radical moves like getting rid of govt debt?

Anders

Ashwin - thanks for the Adair Turner link. I don't quite follow his point about the private banking system. Isn't it the case that the massive flood of long-term credit investments, which arose as a result of the boom in structured finance, were to a large extent simply held by banks themselves (albeit in many cases they were initially held in off-BS SIVs but banks were later forced to consolidate them)? Certainly the most systemically disruptive stuff appears to have been the super-senior structured finance tranches of CDOs which banks held on to, despite them being impossible for the market to value. "maturity transformation was simply a tool to enter into a levered carry trade at the taxpayers’ expense" - sorry if I'm being slow but I don't follow this point?

Ashwin

Anders - Excellent point. I completely agree that there is an investment deficit on the part of the corporate sector - probably not just in the UK but in the US and Europe as well. In a purely fiat currency regime, there is no sanctity to the term structure of government debt. I absolutely do believe that most government debt in this structure would be simply T-bills backing deposits. But I'm still skeptical that the growth in corporate investment needs will exceed long-term savings (so long as govt debt issuance is cut down dramatically).

Ashwin

Anders - on the SIVs, CDOs etc think of it this way. After the advent of synthetic CDOs banks could essentially construct a long-tenor bond with a synthetic derivative layered on top, fund it with short-term repo funding, hold it on or off balance sheet and reap the "returns". This process has no size limitations. And given the tail-risk heavy nature of these structures, the losses come much later and in a catastrophic manner. Mervyn King describes it well here http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/speeches/2010/speech455.pdf "the size of the balance sheet is no longer limited by the scale of opportunities to lend to companies or individuals in the real economy. So-called "financial engineering‟ allows banks to manufacture additional assets without limit. And in the run-up to the crisis, they were aided and abetted in this endeavour by a host of vehicles and funds in the so-called shadow banking system, which in the US grew in gross terms to be larger than the traditional banking sector. This shadow banking system, as well as holding securitised debt and a host of manufactured – or "synthetic‟ – exposures was also a significant source of funding for the conventional banking system. Money market funds and other similar entities had call liabilities totalling over $7 trillion. And they on lent very significant amounts to banks, both directly and indirectly via chains of transactions. This has had two consequences. First, the financial system has become enormously more interconnected. This means that promoting stability of the system as a whole using a regime of regulation of individual institutions is much less likely to be successful than hitherto. Maturity mismatch can grow through chains of transactions – without any significant amount being located in any one institution – a risk described many years ago by Martin Hellwig (Hellwig, 1995). Second, although many of these positions net out when the financial system is seen as a whole, gross balance sheets are not restricted by the scale of the real economy and so banks were able to expand at a remarkable pace."

Anders

Thanks Ashwin - as an MMTer, I would certainly agree with you that short term government debt would be a great improvement; however, I am not optimistic that this insight will become mainstream any time soon - on the contrary, the DMO is congratulating itself on having one of the longest weighted-average tenors around. That King piece is interesting but I don't think his account of the events of 2005-8 quite works. He references the expansion and then contraction of the financial system's balance sheet in gross terms, but presumably to a large extent the net movements are more relevant. It would be interesting to see a more 'systemic' account of the period - eg one which focuses on the debit and credit side of the various instruments and activities. For example, it seems that the growth in MMMFs, which was obviously sponsored by banks, may have sucked demand deposits out of banks, which needed to be replaced by more risky wholesale funding - but I'm not sure this account is coherent. Are you interested in Mosler's suggestions? http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/pdfs/Proposals.pdf

LiminalHack

"In a purely fiat currency regime, there is no sanctity to the term structure of government debt." Agreed, but then why hold out the option of longer duration gov bond issuance? Such a thing would only make sense if the bond were non liquid - like one of the ECBs sterilisation accounts. So a PF buying a 20 year bond deposits the money with the government and gets it back in 20 years - the bond is non-transferable. I wonder what rate they'd want to go for that? Which leads on to your point about PFs providing long term finance. The problem with this is that at real growth rates of at best sub 2%, pensions are not a viable socio-economic system. I think it might be wrong to assume sources of long term funding that existed during prior periods of strong real or nominal growth would exist during a period of low or no growth. Regardless of how innovative a hypothetical micro-chaos regime might be, unless the population is growing then there won't be much if any aggregate growth of the type that underpins pensions.

Ashwin

Anders - yes, I am aware of MMT. Obviously their understanding of the monetary system is not far from mine. But I don't endorse many of their proposals. Let's just say that I am a regulation-skeptic, pro-market discipline on banking and in favour of interventions in the household sector that are discretionary rather than proposals like the Employer of Last Resort which IMO will have serious adaptive consequences. On Mervyn King's account, I think its fairly accurate. MMMFs were in fact a primary source of the wholesale funding for the banks themselves.

Ashwin

LiminalHack - the option is only open in case pension savings far exceed corporate needs. The UK is an example where the long maturity of govt debt is partly because of the strong demand from PFs on the long end due to regulatory reasons. When I say pensions, I simply mean that in the absence of defined-benefit systems, each one of us needs to save for retirement. At most times, this involves buying long-tenor investments. This isn't really sensitive to economic growth - its just a asset-liability duration matching exercise.

LiminalHack

My point is that saving for retirement really isn't tenable at growth rates of 0-2%. Regardless of what the regime is an age structure without a base of new workers that always significantly exceeds the apex of future retirees isn't going to deliver, and thus won't exist to provide long term funding.

Ashwin

Are you saying that there will be no corporate investment needs that need long-term funding? If there are, then they can be met by PFs.

LiminalHack

No, I'm saying that people will stop paying into PFs that are predicated on 7% growth (which is what all the 'illustrations of future value' assume) when it becomes clear that its a massive fiction that you can save 5% of your salary for 40 years and expect it to pay for a 20 year retirement at a decent standard of living. And that's assuming you trust such a long term savings plan not to be stolen by the government or inflated away. Forget about the monetary system for a moment - there is no way that a society with a huge and rising dependency ratio could possibly fund such a dream, regardless of how well managed it is. Pensions only make sense with a strongly growing population. Even that is only a necessary but not sufficient condition since an growing population must be underpinned by plenty of untapped energy resources.

Anders

Ashwin, I wasn't thinking about the ELR idea; rather, it was the idea that "the liability side of banking is not the place for market discipline" - ie banks should source all of their liabilities via the govt or central bank, with the only limit being capital adequacy constraints. This seems a compelling proposition - and if you can accept what it entails, it would certainly address a lot of what you are raising in this post.

Ashwin

LiminalHack - so if we simply have a low growth economy, then most corporate investment can simply be funded out of internal accruals etc as it's likely it will mostly just be replacement investing. I'm not making any assumptions on growth or how long people retire for etc. Could be work for 45, retire for 10 for all I know. I'm talking about defined-contribution pensions where the risk of what happens is entirely on the investor - no guarantees.

Ashwin

Anders - as my call for allowing failure in banking shows, I am all for market discipline on the liability side. I don't believe capital adequacy requirements or any regulatory regime can credibly replace market discipline. They can enhance it for sure but they cannot replace it. Most banks can work their way around most regulations you can throw at them.

David Pearson

Ashwin, Maturity transformation by financial intermediaries takes three forms: 1) traditional commercial bank transformation; 2) "normal" transformation on the part of speculators; 3) transformation by speculators resulting directly from targeted Fed policy. The first two are both "organic": they will always exist and are relatively benign. The third is different. It results from what is currently the main transmission mechanism for monetary policy: arbitrage by speculators. The Fed harnesses that arbitrage to create credit demand. It does so by promising a floor on liquidity and a ceiling on s.t. rate volatility. Both amount to free "options" written by the Fed and handed out to "shadow banks". The following premise holds, IMO: "For any free option, the system will engage in behavior that will maximize the value of that option." Speculators increase the value of the rate volatility and liquidity puts by employing the maximum amount of leverage possible on liquidity and maturity transformation. Stemming Fed-driven maturity/liquidity transformation by speculators is not as difficult as it seems. The Fed has only to abandon "transparency" as a policy goal. This would eliminate speculators' arbitrage based on promised policy trajectories. It would re-direct the source of credit demand back towards real economic activity.

JW Mason

Fascinating post. Two points. First, the problem is you'd need some institutional reforms of pension funds and other vehicles for long-term household savings. They may not genuinely need liquid assets, but AFAICT they generally operate as if they do. And you're still going to need intermediaries, since these funds don't have the institutional capacity to deal directly with borrowers. So it seems like a nontrivial challenge to get the long-term savings of the household sector to the long-term financing needs of the household and business sector without something like banks in between. (Of course we used to have an answer to the housing part of this problem, in the form of thrifts, but we got rid of them.) On the other hand, there's a possible solution in definancializing a lot of these flows. I.e. instead of households owning pensions, which own government bonds, just have the government provide retirement income directly via an expanded Social Security system. Or, again, instead of firms paying profits out to households which then make long-term loans back to firms, just reduce payouts and let firms self-finance investment out of retained earnings. It's just the logical next step in your argument. If there's no maturity mismatch, and you don't see liquidity as an important goal in itself, and you don't think frequent revaluations of assets send useful market signals, then there's really no reason not to net out a lot of these flows.

JW Mason

Also, I admit I'm not quite seeing how the arguments of this post, interesting and important as they are, constitute "the case for allowing banks to fail." If the core function of banks is maturity transformation, and we no longer need maturity transformation, then that would seem to be a case for not having banks -- which is quite different from allowing (individual) banks to fail.

Anders

Ashwin - I think the proposal would go as follows; it's not clear to me how banks would circumvent this: 1. institutions licensed to hold customer deposits must pay a few bps for a govt guarantee on these deposits 2. banks may not issue any interest-bearing debt other than gteed deposits, and loans via the interbank system 3. banks must hold loans on their own books and not sell them; they not must not hold any assets off-BS or engage in any secondary market activity This is not anti-private sector; those banks that do a better job of underwriting will deliver a higher ROE, etc

Ashwin

David - I largely agree with you. I guess my point is that there is no economic rationale for supporting 1 and 2 either. I agree that they will persist in all policy regimes and in "natural" doses are not harmful. On the transparency point, I tend to agree. This was similar to what I was getting at in my post comparing regulatory policy to war. If you want to win at war, be unpredictable. IMO this unpredictability necessitates allowing firms to fail and not providing an automatic liquidity backstop. “For any free option, the system will engage in behavior that will maximize the value of that option.” That's very well put - I tend to frame it as "for every commitment, the system will evolve in a manner that maximises the rents from that commitment" but your version is much more elegant and accurate.

Ashwin

JW - Thanks for the comments. Yes we still need intermediaries but this role is asset-management. In Europe for example, some AM firms have already started SME lending in direct competition with banks. Again my experience is largely in Europe but PFs usually don't need deep liquidity a la equities, bonds etc. The sort of liquidity they need can easily be provided by a fund, SPV etc. I don't doubt that in a different regime, many of these firms will need to change in an institutional sense. But IMO it can happen relatively quickly and painlessly. It's largely a human resource realignment. Much of this evolution that I'm banging on about has happened as a result of the death of defined-benefit pensions. Obviously if we move back to that sort of system, the incentive for households to save quite so much for retirement disappears. But it's hard to see either goats or firms adding onto their defined-benefit commitments given ageing populations, slowing growth etc. In my ideal world, the larger part of this contribution comes from firms paying households wages rather than profits. In my opinion (and there's a fair amount of research on this), incumbent firms sooner or later become risk-averse and stop investing in the sort of disruptive ideas that are needed to keep Schumpeterian product innovation going. The resilient solution is constant entry of new firms that threaten the incumbents and force them to either invest or lead to their failure every now and then. If you want a longer-form version of where I'm coming from, try this post https://www.macroresilience.com/2010/08/30/evolvability-robustness-and-resilience-in-complex-adaptive-systems/ . On not having banks at all, that's a valid thought. My only point is that I don't mind bank-like firms trying to maturity transform - I would just prefer that they not be provided with unlimited liquidity backstops etc.

Anders

@Ashwin: "I don’t mind bank-like firms trying to maturity transform – I would just prefer that they not be provided with unlimited liquidity backstops etc" What's wrong with unlimited liquidity backstops provided that they are accompanied by onerous capital requirements (and the credible threat, if the capital requirements are not met, to nationalise, wipe out equity and equitise junior creditors)?

Ashwin

Anders - my answer in a nutshell is that capital requirements can be arbed very easily and real economic capital is incredibly hard if not impossible to compute. For a long form answer, try Steve Waldman's post http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/716.html

Anders

@JWM "instead of firms paying profits out to households which then make long-term loans back to firms, just reduce payouts and let firms self-finance investment out of retained earnings" Self-financing is already huge; I have heard that Brealey Myers quote a figure >90% for US fixed capital formation which is self-funded. But is this economically desirable? I'd submit that it's worth focusing on the sector financial balances and what one thinks this ought to look like. An obvious starting point is that firms ought to have net financial claims on them (debt and equity) and households ought to have net financial assets, representing those claims. (Govt normally also has some debt outstanding providing assets to HH but people don't seem to think govt debt is a good idea.) The way I look at this is that the financial sector has promoted greater financialisation of households, with a greater expectation that one's own pot of capital will need to suffice to fund pensions and other contingencies, and less reliance on the state for these things. But for households to accumulate a larger pot of net financial assets relative to GDP implies that firms must be willing to run a larger financial deficit, raising capital to fund investment over and above their retained earnings. I see a tension here: households spending less by definition worsens the outlook for firms, lowering their willingness to drive fixed capital formation. Perhaps this is a relevant way to analyse the ballooning govt debt in the last couple of years, as bridging the gap between the two. One interpretation would be that we should reverse household financialisation, increasing state pension provision (in line with your suggestion) and thus making households spend more out of current income; this would help to spur fixed capital formation, which is probably a better equilibrium for long-term GDP growth.

Anders

@Ashwin: "real economic capital is incredibly hard if not impossible to compute" Yes, but only assuming deposit-taking institutions are permitted to do these complex things. If banks' activities were simpler, capital adequacy restrictions ought to become meaningful.

Anders

Fascinating discussion at FTAV - people (incl Larry Fink) are commenting on how cash-rich corporates are lending themselves, disintermediating the banks.

Ashwin

Anders - given how complex the sphere of "banking" activities has become, I'm just skeptical that any such simplification can be achieved in an effective manner. But still I'd rather adopt Mosler's rules than stick with the current system. At any rate, my point that the exercise of maturity transformation doesn't provide any economic value still holds which means that deposit protection is still unnecessary. Just back all deposits with T-bills. If you could give me a link to that FTAV discussion, that would be great. Thanks for all the comments.

scepticus

ashwin, here you go: http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2011/10/14/702751/markets-live/

Ashwin

scepticus - thank you!

K

Ashwin, Fully agree with everything you say here. What is doubtful, of course, is the idea that if we just remove the regulatory support for maturity transformation, then the resulting system (with lots of small bank failures and lots of new ones starting up) will be economically efficient. I think I'd be spending way to much of my time monitoring the health of the available banks and shifting funds around. Doesn't sound like fun. What government needs to do is to extend the central bank services to all citizens and corporations. More than adequate money supply could be created simply by investors repoing their liquid assets (there'd be lots of bank bonds and equity!) with a *very* safe haircut (e.g. 70% for liquid stocks, 50% for liquid corporate/bank bonds, 1%-20% for government bonds depending on maturity) at the CB. Creation of money does *not* require maturity transformation of illiquid assets. Repoing liquid ones will do the trick. Also, if everybody is using central bank money we'd need *way less* of it. That's because settlements could be carried out much, much faster than the abysmal current system of interbank cheque clearing.

Ashwin

K - in a maturity-transformation free system, I'm convinced that the demand for risk-free deposits can be backed by risk-free t-bills. Of course, if you want extra return, you need to take risk. And the growth of money-market mutual funds tells us that a lot of people wanted extra return. My objection is with this extra return being achieved in a taxpayer-guaranteed manner.

K

I agree with the basic purpose of eliminating agency problems. Deposit insurance is a huge one. And I agree that the demand for risk free deposits could be covered by t-bills. But given the amount of crap that got stuffed into AAA money market instruments (LSS trades!) that earned 10 bps over t-bills I don't think money market/deposit clients have the ability to look out for their own interests. In which case I'm not sure the demand for the risk free deposits and the t-bills will find each other. In which case we'll end up with bank runs all over the place. Buyer beware and all, of course. But I think it might be more efficient to help people. And rather forcing the deposits and the t-bills together (100% reserves) I prefer to let the banks be free but to give people the option of leaving their deposits at the Fed just like the banks do. That way they don't have to think too much. Same services for everyone (banks, corps and retail) and everyone can be free of regulation.

Ashwin

K - Yes, I expect the risk-free system to look somewhat like the old Postal Savings system http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Postal_Savings_System . All other investment options need to be explicitly risky and marked to market. I don't mind regulations to protect the small investor - I only object to these regulations being the quid pro quo for an implicit bailout commitment.

K

Ashwin: "I expect the risk-free system to look somewhat like the old Postal Savings" Cool! Nothing new under the sun... "All other investment options need to be explicitly risky and marked to market." Yup. Also prevents products with high embedded fees from being marketed as par instruments. "I don’t mind regulations to protect the small investor" I do. They don't actually protect anybody. They just provide the dealer with cover, or appearance of propriety. And the regulations end up being drafted by the industry and serve principally to protect them from actual fraud laws. It's like putting a sign on a beach saying: The sharks here are prohibited from eating humans. Swimming is mandatory. The Federation of Sharks Unfortunately people see the sign and think "Wow! Nice sharks!" The industry needs to be disciplined by the same fraud laws that apply to everyone else. Sometimes you got to kill a few sharks. "I only object to these regulations being the quid pro quo for an implicit bailout commitment." Especially galling when the regulations are actually a subsidy rather than a cost overall.

Ashwin

K - it seems we are in agreement. I'm not a fan of regulations that serve as entry barriers to small players or as cover for avoiding fraud laws either. And yes I have long since figured out that none of my ideas are in the least bit new, simply long forgotten!

scepticus

"What government needs to do is to extend the central bank services to all citizens and corporations. " Agree with that. And its started, with companies like Siemens taking control of their own financial destiny, Of course the flip side is that the CB gives up any notion of controlling the price level. K, are you familiar with www.ripplepay.org?

K

Scepticus: "Of course the flip side is that the CB gives up any notion of controlling the price level." I don't think so. They can still set the rate on the deposits on their balance sheet. But more importantly, there is still going to be a demand for risk free loans. This is principally repo loans from low risk tolerance to high risk tolerance agents. And the central bank can always set that rate. And that's the rate that determines the whole risk free term structure. I hadn't seen Ripple Pay. It's pretty cool. But it's credit risky money and iit looks to me like it's got lots of potential for systemic "bank" runs. I'd prefer to keep my money at the CB and, like Ashwin says, there ought to be enough risk free t-bills to support the demand for safe money. But by all means, if people want it and it gets credit to people (without them risking getting their knees broken), I'm all for it.

scepticus

K, I do think so. If actors are netting credit between one another and then just using the CB to clear the residual without using any other intermediaries then the CB has no control over the amount of credit created. If individuals now have access to the central bank then in effect individuals are banks and can create and clear credit between themselves without necessitating transfers via the CB. That's what ripple is about. The whole process of dis-intermediation implies that the CB will not be able to control credit creation. They can control as you say certain types of loan but that's only useful if that type dominates in the wider credit market. If they make said loans expensive then the wider market can just route around the CB. We can only say the CB has control of the price level if it has effective levers to both decrease and increase the price of money.

K

Scepticus: But the CB pays the risk free rate on deposits. Why would anybody lend below that rate? They may lend higher. Everybody will seek the cheapest source of funds in a competitive lending market. So they end up paying the risk free rate plus a credit spread that depends on their credit worthiness. But that's a lot like the system we have right now, except with a totally decentralized commercial banking sector.

scepticus

People will lend and borrow below the risk free rate if the CB has set the rate high enough to restrict liquidity such that actors who wish to transact now cannot do so profitably. In the traditional system if you want to engage in credit operations that can be cleared using the CB clearing mechanism then you had to go to a commercial bank, who as you rightly point out won't engage if the terms are below the risk free rate This is because the bank intermediary exists to make profits intermediating. Thus the CB can control price levels by making certain transactions impossible by dint of their being a greedy intermediary involved. Now this intermediary is no longer there, two parties whose transaction profits are not based on the act of lending (but are based on moving goods and services) may establish a line of credit using the CB clearing mechanism. If the two parties agree on a rate which is below the CB risk free rate, then the creditor will simply remit the difference it earned in interest back to the borrower. Note that these trading parties will definitely engage in extending credit below the "risk free" rate if they both profit by doing so.

K

Scepticus: I think I can see how in a world where the provision of credit is inextricably linked with goods transactions, we can no longer speak of a market for credit. And I have no idea how such a complex network of trust and transactions would behave. But it doesn't sound good to me. I prefer to imagine, and I think it's closer to the truth, that there is a market of agents who can provide me with credit which is quite different from the market of people who can provide me with bread and that the local grocer is in no way privileged in his knowledge of my trustworthiness or in his ability to collect. A history of trustworthiness can be kept either through a market mechanism (credit score) or via a community rating mechanism (like E-Bay). Only in the market for some capital goods (e.g. cars), where the seller has particular expertize in the remarketing of a recovered asset, do I see any kind of link between credit and goods. And even then, I can get a competitive loan from the bank if the LTV is low. Also, I'm very skeptical of how your system, being 100% inside money, escapes a cumulative Wicksellian catastrophe. If your economy is growing it has a positive natural rate. In the absence of interest, the limiting factor on money growth will be hard credit limits, i.e. financial repression. I think you will end up with inflationary bubbles followed by money shortages and collapse of trade (depression).

scepticus

"Scepticus: I think I can see how in a world where the provision of credit is inextricably linked with goods transactions, we can no longer speak of a market for credit." I am thinking of a case where Siemens, a bank, and also an industrial conglomerate, wishes to shift some white goods. They will extend credit to both their retail channel and the end consumer who buys their products, at an interest rate they see fit, regardless of what the CB thinks is a suitable base rate. At the same time they would net credit with their suppliers. A circular route from a supplier owed credit and a consumer who owes siemens might easily be found and netted without going via the CB, and even if it did go via the CB it needn't use the official rate. As for systems I have outlined - I wasn't aware I had outlined one. I merely pointed out that any and all transactions not needing *significant* maturity transformation (say beyond one or two years) need not go via intermediaries and can be directly peer-2-peer hence removing any scope for centralised control of the terms and conditions of those credit agreements.

K

"They will extend credit to both their retail channel and the end consumer who buys their products, at an interest rate they see fit, regardless of what the CB thinks is a suitable base rate" I doubt it. They may charge less than the risk free rate but add the cost of that to the sale price. But if the risk free rate goes up, the cost of loans will follow. Otherwise Siemens is stupid since they could lend for more elsewhere. Independently, there's a minimum price they'll sell at and a minimum rate they'll lend at (which is above the risk free rate). If the sale and the loan are bundled together, you can split the saleprice and the rate any number of ways without changing the NPV of the transaction. But there's no way you'll buy the product at cost and get a loan below the risk free rate, or the seller is allowing themselves to be arbitraged.

scepticus

"I doubt it. They may charge less than the risk free rate but add the cost of that to the sale price. But if the risk free rate goes up, the cost of loans will follow. Otherwise Siemens is stupid since they could lend for more elsewhere. " If the vast majority of siemens' profits come from selling industrial and consumer goods then what it makes from lending is immaterial. As I have pointed out twice now, they are only lending in order to shift their goods. What you seem to be suggesting is that a series of fully dis-intermdiated non-bank firms will somehow in aggregate obey the wishes of the CB that they reduce their profits below best. I cam't see why a rise in the risk free rate would cause profit maximising non bank firms to reduce their volume of sales and profits when that rate doesn't actually constitute a barrier to transacting (as it did when all firms and individuals were intermediated by banks).

K

Looks like too much work to find agreement and OT. Guess we'll have to leave it at that.

scepticus

haha, fair point. It is indeed OT in this thread however it is I'm sure you'd agree really a rather fundamental issue that relates directly to the central theme of ashwin's blog.

The Public Deposit Option: An Alternative To “Regulate and Insure” Banking at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] match long-term investment projects, such projects would not find adequate funding. But as I have argued and the data shows, household long-term savings (which includes pensions and life insurance) is [...]

interfluidity » Time and interest are not so interesting

[...] needed to mediate exchanges across time of the right to use real resources. As Ashwin Parameswaran points out, there is no great mismatch between individuals’ willingness to save long-term and [...]

Unifying The Fiscal And Monetary Functions: A Policy Proposal at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] large chunk of the present demand for long-term borrowing comes from the government(see this post for data). Unlike the private sector for whom the avoidance of refinancing risk is worth issuing [...]

Hedge fund manager Ken Griffin: Break up the megabanks | AEIdeas

[...] match long-term investment projects, such projects would not find adequate funding. But as I have argued and the data shows, household long-term savings (which includes pensions and life insurance) is [...]