The Cause and Impact of Crony Capitalism: the Great Stagnation and the Great Recession

STABILITY AS THE PRIMARY CAUSE OF CRONY CAPITALISM

The core insight of the Minsky-Holling resilience framework is that stability and stabilisation breed fragility and loss of system resilience . TBTF protection and the moral hazard problem is best seen as a subset of the broader policy of stabilisation, of which policies such as the Greenspan Put are much more pervasive and dangerous.

By itself, stabilisation is not sufficient to cause cronyism and rent seeking. Once a system has undergone a period of stabilisation, the system manager is always tempted to prolong the stabilisation for fear of the short-term disruption or even collapse. However, not all crisis-mitigation strategies involve bailouts and transfers of wealth to the incumbent corporates. As Mancur Olson pointed out, society can confine its "distributional transfers to poor and unfortunate individuals" rather than bailing out incumbent firms and still hope to achieve the same results.

To fully explain the rise of crony capitalism, we need to combine the Minsky-Holling framework with Mancur Olson's insight that extended periods of stability trigger a progressive increase in the power of special interests and rent-seeking activity. Olson also noted the self-preserving nature of this phenomenon. Once rent-seeking has achieved sufficient scale, "distributional coalitions have the incentive and..the power to prevent changes that would deprive them of their enlarged share of the social output".

SYSTEMIC IMPACT OF CRONY CAPITALISM

Crony capitalism results in a homogenous, tightly coupled and fragile macroeconomy. The key question is: Via which channels does this systemic malformation occur? As I have touched upon in some earlier posts [1,2], the systemic implications of crony capitalism arise from its negative impact on new firm entry. In the context of the exploration vs exploitation framework, absence of new firm entry tilts the system towards over-exploitation ((It cannot be emphasized enough that absence of new firm entry is simply the channel through which crony capitalism malforms the macroeconomy. Therefore, attempts to artificially boost new firm entry are likely to fail unless they tackle the ultimate cause of the problem which is stabilisation)) .

Exploration vs Exploitation: The Importance of New Firm Entry in Sustaining Exploration

In a seminal article, James March distinguished between "the exploration of new possibilities and the exploitation of old certainties. Exploration includes things captured by terms such as search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, innovation. Exploitation includes such things as refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, execution." True innovation is an act of exploration under conditions of irreducible uncertainty whereas exploitation is an act of optimisation under a known distribution.

The assertion that dominant incumbent firms find it hard to sustain exploratory innovation is not a controversial one. I do not intend to reiterate the popular arguments in the management literature, many of which I explored in a previous post. Moreover, the argument presented here is more subtle: I do not claim that incumbents cannot explore effectively but simply that they can explore effectively only when pushed to do so by a constant stream of new entrants. This is of course the "invisible foot" argument of Joseph Berliner and Burton Klein for which the exploration-exploitation framework provides an intuitive and rigorous rationale.

Let us assume a scenario where the entry of new firms has slowed to a trickle, the sector is dominated by a few dominant incumbents and the S-curve of growth is about to enter its maturity/decline phase. To trigger off a new S-curve of growth, the incumbents need to explore. However, almost by definition, the odds that any given act of exploration will be successful is small. Moreover, the positive payoff from any exploratory search almost certainly lies far in the future. For an improbable shot at moving from a position of comfort to one of dominance in the distant future, an incumbent firm needs to divert resources from optimising and efficiency-increasing initiatives that will deliver predictable profits in the near future. Of course if a significant proportion of its competitors adopt an exploratory strategy, even an incumbent firm will be forced to follow suit for fear of loss of market share. But this critical mass of exploratory incumbents never comes about. In essence, the state where almost all incumbents are content to focus their energies on exploitation is a Nash equilibrium.

On the other hand, the incentives of any new entrant are almost entirely skewed in favour of exploratory strategies. Even an improbable shot at glory is enough to outweigh the minor consequences of failure ((It is critical that the personal consequences of firm failure are minor for the entrepreneur - this is not the case for cultural and legal reasons in many countries around the world but is largely still true in the United States.)) . It cannot be emphasised enough that this argument does not depend upon the irrationality of the entrant. The same incremental payoff that represents a minor improvement for the incumbent is a life-changing event for the entrepreneur. When there exists a critical mass of exploratory new entrants, the dominant incumbents are compelled to follow suit and the Nash equilibrium of the industry shifts towards the appropriate mix of exploitation and exploration.

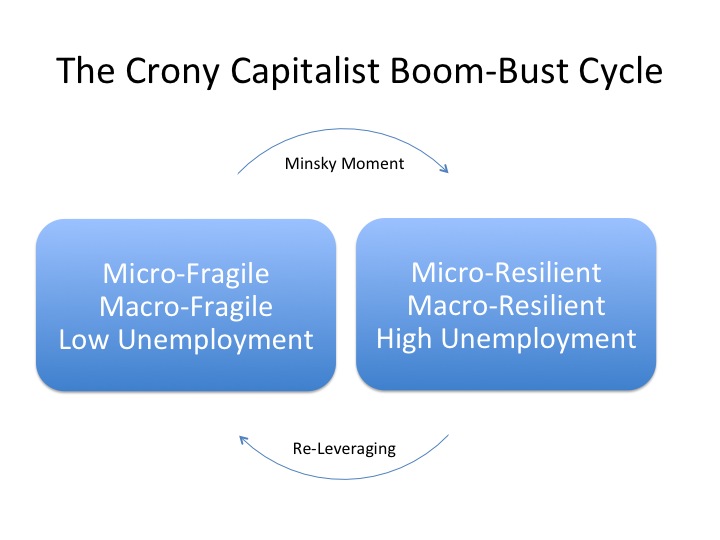

The Crony Capitalist Boom-Bust Cycle: A Tradeoff between System Resilience and Full Employment

Due to insufficient exploratory innovation, a crony capitalist economy is not diverse enough. But this does not imply that the system is fragile either at firm/micro level or at the level of the macroeconomy. In the absence of any risk of being displaced by new entrants, incumbent firms can simply maintain significant financial slack ((It could be argued that incumbents could follow this strategy even when new entrants threaten them. This strategy however has its limits - an extended period of standing on the sidelines of exploratory activity can degrade the ability of the incumbent to rejoin the fray. As Brian Loasby remarked : "For many years, Arnold Weinberg chose to build up GEC's reserves against an uncertain technological future in the form of cash rather than by investing in the creation of technological capabilities of unknown value. This policy, one might suggest, appears much more attractive in a financial environment where technology can often be bought by buying companies than in one where the market for corporate control is more tightly constrained; but it must be remembered that some, perhaps substantial, technological capability is likely to be needed in order to judge what companies are worth acquiring, and to make effective use of the acquisitions. As so often, substitutes are also in part complements.")). If incumbents do maintain significant financial slack, sustainable full employment is impossible almost by definition. However, full employment can be achieved temporarily in two ways: Either incumbent corporates can gradually give up their financial slack and lever up as the period of stability extends as Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH) would predict, or the household or government sector can lever up to compensate for the slack held by the corporate sector.

Most developed economies went down the route of increased household and corporate leverage with the process aided and abetted by monetary and regulatory policy. But it is instructive that developing economies such as India faced exactly the same problem in their "crony socialist" days. In keeping with its ideological leanings pre-1990, India tackled the unemployment problem via increased government spending. Whatever the chosen solution, full employment is unsustainable in the long run unless the core problem of cronyism is tackled. The current over-leveraged state of the consumer in the developed world can be papered over by increased government spending but in the face of increased cronyism, it only kicks the can further down the road. Restoring corporate animal spirits depends upon corporate slack being utilised in exploratory investment, which as discussed above is inconsistent with a cronyist economy.

Micro-Fragility as the Key to a Resilient Macroeconomy and Sustainable Full Employment

At the appropriate mix of exploration and exploitation, individual incumbent and new entrant firms are both incredibly vulnerable. Most exploratory investments are destined to fail as are most firms, sooner or later. Yet due to the diversity of firm-level strategies, the macroeconomy of vulnerable firms is incredibly resilient. At the same time, the transfer of wealth from incumbent corporates to the household sector via reduced corporate slack and increased investment means that sustainable full employment can be achieved without undue leverage. The only question is whether we can break out of the Olsonian special interest trap without having to suffer a systemic collapse in the process.

Comments

praxis22

Really excellent bit of work that, in fact it's so good I'm going to read it again :)

David Merkel

Bravo. Loved every bit.

Bruce Wilder

Wow! You are packing a lot of good stuff into this synthesis. You have good taste in your selection of ingredients, but you've made the argument very dense. Not that I'm complaining, exactly. Bravo!

Ashwin

praxis22 - Thank you! David - Thanks. I respect your opinion enormously so glad you liked it! Bruce - I was a bit concerned about the density. The original piece I wrote was 3 or 4 times as long but I thought it was way too meandering. There are 5-10 posts coming on the back of this which will hopefully expand on the theme and apply it to some market/economic phenomena.

Michael Strong

Brilliant as always, Ashwin. I'd love to find a way to get a much broader readership for your work. But the really knotty question is, "How can we prevent existing firms from successfully supporting legislation that prevents new entrants?" My perception is that there are countless subtle ways to create barriers to entry, and that as long as we have widespread public support for regulation, concentrated interests (here in the financial industry) will find ways to create barriers to entry which are prima facie based on legitimate regulatory concerns. See Bruce Yandle's work on Bootleggers and Baptists for the basic strategy used by such interests, http://www.cato.org/pubs/regulation/regv7n3/v7n3-3.pdf

Ashwin

MIchael - Thanks. I can't say that I've tried too hard to get a broader readership but always willing to listen to ideas! I've read the Bootleggers/Baptists article and I agree completely. More generally, I think even Olson was too optimistic that once the cost of rent-seeking to society became too high, it would limit itself. It seems quite plausible to me that it may even take an event of collapse to fuel radical change.

The Great Recession through a Crony Capitalist Lens at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] this post, I apply the framework outlined previously to some empirical patterns in the financial markets and the broader economy. The objective is not [...]

Bruce Wilder

I'm afraid I'm not much a fan of the story of rivals in oligopoly, or new entrants and barriers to entry. It made intuitive sense in the American industrial markets of the 1950s, but it was always just story-telling and hand-waving; there were no analytical models to back it up. For the field of industrial organization, it was a dead-end. In the 21st century, using "monopoly" as a pejorative doesn't get us very far. The competition is no longer auto and steel dinosaurs. We're in the age of contestable markets, where competition is aimed specifically at capturing "monopolies": Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook, E-bay, Amazon, Adobe, etc., etc. The rivalrous "new entrant" can be conjured only as a vague threat; I suppose it is still an element in play, but, as a practical matter, I don't think there's an obvious policy intervention by the state, which is not likely to go terribly wrong. As much as I despise Microsoft, I wouldn't blithely dismiss the network economies that its "monopoly" delivers. And, though I can see the enormous diseconomies and hazards of scale in the things Microsoft -- and its rivals IBM, Apple, Google, Adobe -- attempt, I wouldn't dismiss the need for some large organizations to attempt some large-scale tasks. So, let all that go, for a moment. Rather than focus on the "new entrant" / oligopoly horizontal competition model, I'd suggest backing up a bit, and considering vertical and network competition/negotiation models: the vision of the micro-economy as a network of relationships, which are both cooperative and antagonistic, involving both negotiation and competition. The micro-economy, in the kind of abstract terms you want to use, depends for its vitality on an effective balance of conflict and cooperation in "competition" between independent firms, and that "competition" has to be understood as forming a multi-dimensional net; "horizontal" rivalry is only one, often incidental dimension. Not just price discovery, but the discovery and verification of lots of information depends upon the integrity of "competition" in the form of, say, so-called arm's length negotiations, or the willingness of an auditor to walk away from a bribe. If a conglomerate is on both sides of the negotitiating table, such that an executive can make an adminstrative choice, to serve the executive's strategic interest, well, then we have a problem. As important sectors of the U.S. economy have become progressively more scelrotic, it is the erosion of the "integrity" of "market" "competition", which has been most salient. This was on full display in the financial sector, as universal banks combined functions in ways that put the same corporation on both sides of negotiations. It isn't "entry", which is the per se problem; it is integrity, the integrity, which requires separation of strategic control. It's the problem of a financial auditor, which no longer maintains professional standards or strategic independence from the management. (See Arthur Anderson and Enron.) It is a ratings agency, whose strategic choices and incentives are manipulated to undermine its integrity. It's the change in FCC rules, which previously limited the ability of television networks to own production companies. It is merging NBC and Comcast. It's removing the effective prohibitions on resale price maintenance. I don't remember the extent to which Mancur Olson highlighted this, but what used to limit rent-seeking lobbying in Congress was the conflicts between firms and industries and unions and professional associations. Conflict was the key to keeping it down to a dull roar. As long a politician could play the railroads against the trucking companies, the savings and loans against the banks, the UAW against the automakers, the politician had a means of maintaining her strategic independence, and the lobbyists limited each others' effectiveness. The railroads had to match the truckers, the railway unions the Teamsters, but their was no percentage in ratcheting up the competition, as long they tended to cancel each other out. I think your intuitions about the relationship between predatory capitalism and macro-stability are pretty good. But, "new entry" and exploration/exploitation isn't the money shot you are looking for. I'd suggest that the integrity of interaction (cooperation, rivalry, negotiation, regulation) of independent loci of control and discretion in the decentralized "market" economy is the bigger, more pervasive, more general target. Think about how the emergence of Media conglomerates has intensified Washington rent-seeking in that sector, dumbed down opinion and news dissemination, promoted endless re-makes of bad movies (Tron? Are you kidding me?) and global franchises in cheesy teevee show concepts. Politico.com, which isn't itself a giant, exemplifies how network strategies undermine the independence and integrity of news and opinion production in this environment. They place their reporters on cable news and network public affairs shows and the PBS shows, and pretty soon, their point of view is both pervasive and given an establishment imprimatur; "entry" is involved, since they've taken one of a limited number of seats at every venue, but that barely scratches the surface on what's wrong with this kind of corporate homogenization. I've tried to give a bunch of examples, in place of a more detailed theory; I hope that reinforces, rather than distracts from my general point. There is some theory, from, say, Stiglitz, which ties firm-level leverage to incentives and organization for management control. The hard part may be understanding the role of rents in organizing the firm's management and control structure. There's definitely a shift toward exploitation, and away from technical efficiency gains, as financialization takes over. And, getting the leverage right, or wrong, at the firm level suggests several channels to macro/financial issues. I'm going to be thinking about this for a while; I see a whole web of connections that might fill in, for me.

Ashwin

Bruce - on the importance of "integrity" in a market economy, I'm with you. Cronyism does immeasurable damage here - once you go down the slippery slope where every market participant has to assume the worst of others all the time, its very difficult to come back. Many cronyist developing economies are defined by the distrust that pervades economic dealings. I look at absence of new entry as a symptom of a malformed economy. Tackling the disease demands that we look at the root cause which is rent extraction and stabilisation. If rents are present, then rent extraction is the "dominant niche" in the industry and even new entrants will simply focus on rent extraction rather than adding to the diversity via exploratory activity. On the impact of conflicting lobbies, that is a very long answer which will be part of a post I hope to put up in the next week or so.

The Different Shades of Crony Capitalism at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] previous posts (1,2), I explained how crony capitalism and rent-seeking can explain many of our current economic [...]

Links III « Einar Gislason

[...] The Cause and Impact of Crony Capitalism: the Great Stagnation and the Great Recession [...]

The Great Stagnation and Special Interests at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] the last couple of months, I wrote three posts [1,2,3] that tried to explain our recent economic experience as a consequence of the increased [...]

Roger G Lewis

Fantastic article like another poster has commented I will be re reading and gently absorbing the subtleties for several days to come. I am very drawn to the cronyism arguments and paradox of free market propaganda and oligarchic / monopolistic barriers to trade. The basis of so much economic forecasting is also institutionalising the bias in terms of client bias going unchecked on the framing of the deterministic variables in economic models ( where is the peer review?) both Private and Government algorithms are quite capable of being very self serving. I also have an interest in this area on Climate forecasting and the narratives that flow from ignorance of what the predictive science/art is about, what Michael Perleman calls procrustean analysis. Across a whole slew of public policy the precautionary principle is emerging as a theme in a most Dystopian narrative you really couldn't make it up!

Ashwin

Roger - Thanks. I hope we don't end up in a dystopia but it's hard to see lasting change come in an orderly fashion.

Macroeconomic Stabilisation and Financialisation in The Real Economy at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] Some Post-Keynesian and Marxian economists also claim that this process of financialisation is responsible for the reluctance of corporates to invest in innovation. As Bill Lazonick puts it, “the financialization of corporate resource allocation undermines investment in innovation”. This ‘investment deficit’ has in turn led to the secular downturn in productivity growth across the Western world since the 1970s, a phenomenon that Tyler Cowen has coined as ‘The Great Stagnation’. This thesis, appealing though it is, is too simplistic. The increased market-sensitivity combined with the macro-stabilisation commitment encourages low-risk process innovation and discourages uncertain and exploratory product innovation. The collapse in high-risk, exploratory innovation is exacerbated by the rise in the influence of special interests that accompanies any extended period of stability, a dynamic that I discussed in an earlier post. [...]

Innovation, Stagnation and Unemployment at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] robust stream of new entrants into the industry. I outlined the rationale for this in a previous post: Let us assume a scenario where the entry of new firms has slowed to a trickle, the sector is [...]

Steve Roth

Also planning to re-read more than once, thanks. Question: can legislated redistribution break the cycle? Transferring money hence power to non-incumbents? Yeah I get that incumbents will fight it and they have the money/power to do so, but there's some redistribution now and could be more (or less). Some countries have more, some less. The countries that have more also have much higher intergenerational income mobility. Hey I'm grasping at straws here, vague scraps of hope that Jazzbumpah isn't perfectly accurate in his repeated mantra: "We are so f***ed." Toss me something that floats. Please.

Ashwin

Steve - Thanks. Redistribution makes the system more equitable but it needs to be a constant process and ever-increasing if it needs to compensate for the growing creep of rent-extraction in an Olsonian stable period. I can't really see how this would be achieved in an already cronyist system in a democratic manner. I'm not a fan of "revolutions" or economic collapse but I can't really see any other end-result. In fact, I consider redistribution to be a partly orthogonal issue to the issue of cronyism. The Scandinavian model is built on a much less cronyist but much more redistributive philosophy - too often, free market rhetoric simply masks a corporatist agenda. Also if the objective is long-term Schumpeterian growth, then the destruction in the 'creative destruction' is important. Incumbent firms need to feel the heat at all times and there is no substitute for business failure. Apologies for not coming up with anything hopeful!

Steve Roth

Thanks Ashwin. I don't understand the connection between the first and second parts of this sentence: "The Scandinavian model is built on a much less cronyist but much more redistributive philosophy – too often, free market rhetoric simply masks a corporatist agenda." Excuse my slowness -- too big a leap for me. A sentence or two of explanation? Thanks.

Ashwin

Steve - Apologies. I'm the one who's being obtuse. The second part is a comment on the United States. I remember my thoughts differently from how that sentence came out :-). I made a comment on this post https://www.macroresilience.com/2010/10/18/the-resilience-stability-tradeoff-drawing-analogies-between-river-management-and-macroeconomic-management/ that "it is not limiting handouts to the poor that defines a free and dynamic economy but limiting rents that flow to the privileged." By this definition, I consider say Denmark to be far more "free-market" than the United States.

Steve Roth

I'm with you on that. As I mentioned, intergenerational mobility -- newcomers replacing incumbents -- is far higher in those countries. And those countries give me hope. If we could just be "freed of the Southern incubus..." http://www.asymptosis.com/freed-of-the-southern-incubus.html

The Control Revolution And Its Discontents at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] are scarce but also because slack at the individual and corporate level is a significant cause of unemployment. Such near-optimal robustness in both natural and economic systems is not achieved with [...]

Chicago Boyz » Blog Archive » Institutions, Instruments, and the Innovator’s Dilemma

[...] See Ashwin Parameswaran, “Cause and Impact of Crony Capitalism: The Great Stagnation and the Great Recession“, MacroEconomic Resilience, (24 November 2010) for a longer (and denser!) explanation of this [...]