Critical Transitions in Markets and Macroeconomic Systems

This post is the first in a series that takes an ecological and dynamic approach to analysing market/macroeconomic regimes and transitions between these regimes.

Normal, Pre-Crisis and Crisis Regimes

In a post on market crises, Rick Bookstaber identified three regimes that any model of the market must represent (normal, pre-crisis and crisis) and analysed the statistical properties (volatility,correlation etc) of each of these regimes. The framework below however characterises each regime by the varying combinations of positive and negative feedback processes and the variations and regime shifts are determined by the adaptive and evolutionary processes operating within the system.

1. Normal regimes are resilient regimes. They are characterised by a balanced and diverse mix of positive and negative feedback processes. For every momentum trader who bets on the continuation of a trend, there is a contrarian who bets the other way.

2. Pre-crisis regimes are characterised by an increasing dominance of positive feedback processes. An unusually high degree of stability or a persistent trend progressively weeds out negative feedback processes from the system thus leaving it vulnerable to collapse even as a result of disturbances that it could easily absorb in its previously resilient normal state. Such regimes can arise from bubbles but this is not necessary. Pre-crisis only implies that a regime change into the crisis regime is increasingly likely - in ecological terms, the pre-crisis regime is fragile and has suffered a significant loss of resilience.

3. Crisis regimes are essentially transitional - the disturbance has occurred and the positive feedback processes that dominated the previous regime have now reversed direction. However, the final destination of this transition is uncertain - if the system is left alone, it will undergo a discontinuous transition to a normal regime. However, if sufficient external stabilisation pressures are exerted upon the system, it may revert to the pre-crisis regime or even stay in the crisis regime for a longer period. It’s worth noting that I define a normal regime only by its resilience and not by its desirability - even a state of civilizational collapse can be incredibly resilient.

"Critical Transitions" from the Pre-Crisis to the Crisis Regime

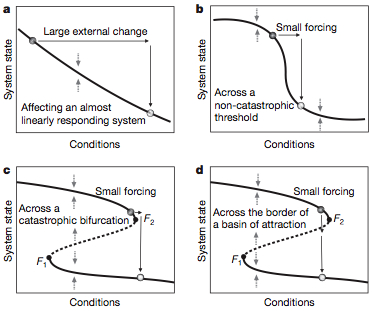

In fragile systems even a minor disturbance can trigger a discontinuous move to an alternative regime - Marten Scheffer refers to such moves as "critical transitions". Figures a,b,c and d below represent a continuum of ways in which the system can react to changing external conditions (ref Scheffer et al) . Although I will frequently refer to "equilibria" and "states" in the discussion below, these are better described as "attractors" and "regimes" given the dynamic nature of the system - the static terminology is merely a simplification.

In Figure a, the system state reacts smoothly to perturbations - for example, a large external change will trigger a large move in the state of the system. The dotted arrows denote the direction in which the system moves when it is not on the curve i.e. in equilibrium. Any move away from equilibrium triggers forces that bring it back to the curve. In Figure b, the transition is non-linear and a small perturbation can trigger a regime shift - however a reversal of conditions of an equally small magnitude can reverse the regime shift. Clearly, such a system does not satisfactorily explain our current economic predicament where monetary and fiscal intervention far in excess of the initial sub-prime shock have failed to bring the system back to its previous state.

Figure c however may be a more accurate description of the current state of the economy and the market - for a certain range of conditions, there exist two alternative stable states separated by an unstable equilibrium (marked by the dotted line). As the dotted arrows indicate, movement away from the unstable equilibrium can carry the system to either of the two alternative stable states. Figure d illustrates how a small perturbation past the point F2 triggers a "catastrophic" transition from the upper branch to the lower branch - moreover, unless conditions are reversed all the way back to the point F1, the system will not revert back to the upper branch stable state. The system therefore exhibits "hysteresis" - i.e. the path matters. The forward and backward switches occur at different points F2 and F1 respectively, which implies that reversing such transitions is not easy. A comprehensive discussion of the conditions that will determine the extent of hysteresis is beyond the scope of this post - however it is worth mentioning that cognitive and organisational rigidity in the absence of sufficient diversity is a sufficient condition for hysteresis in the macro-system.

Before I apply the above framework to some events in the market, it is worth clarifying how the states in Figure d correspond to those chosen by Rick Bookstaber. The "normal" regime refers to the parts of the upper and lower branch stable states that are far from the points F1 and F2 i.e. the system is resilient to a change in external conditions. As I mentioned earlier, normal does not equate to desirable - the lower branch could be a state of collapse. If we designate the upper branch as a desirable normal state and the lower branch as an undesirable one, then the zone close to point F2 on the upper branch is the pre-crisis regime. The crisis regime is the short catastrophic transition from F2 to the lower branch if the system is left alone. If forces external to the system are applied to prevent a transition to the lower branch, then the system could either revert back to the upper branch or even stay in the crisis regime on the dotted line unstable equilibrium for a longer period.

The Magnetar Trade revisited

In an earlier post, I analysed how the infamous Magnetar Trade could be explained with a framework that incorporates catastrophic transitions between alternative stable states. As I noted: "The Magnetar trade would pay off in two scenarios – if there were no defaults in any of their CDOs, or if there were so many defaults that the tranches that they were short also defaulted alongwith the equity tranche. The trade would likely lose money if there were limited defaults in all the CDOs and the senior tranches did not default. Essentially, the trade was attractive if one believed that this intermediate scenario was improbable...Intermediate scenarios are unlikely when the system is characterised by multiple stable states and catastrophic transitions between these states. In adaptive systems such as ecosystems or macroeconomies, such transitions are most likely when the system is fragile and in a state of low resilience. The system tends to be dominated by positive feedback processes that amplify the impact of small perturbations, with no negative feedback processes present that can arrest this snowballing effect."

In the language of critical transitions, Magnetar calculated that the real estate and MBS markets were in a fragile pre-crisis state and no intervention would prevent the rapid critical transition from F2 to the lower branch.

"Schizophrenic" Markets and the Long Crisis

Recently, many commentators have noted the apparently schizophrenic nature of the markets, turning from risk-on to risk-off at the drop of a hat. For example, John Kemp argues that the markets are "trapped between euphoria and despair" and notes the U-shaped distribution of Bank of England's inflation forecasts (table 5.13). Although at first glance this sort of behaviour seems irrational, it may not be - As PIMCO's Richard Clarida notes: "we are in a world in which average outcomes – for growth, inflation, corporate and sovereign defaults, and the investment returns driven by these outcomes – will matter less and less for investors and policymakers. This is because we are in a New Normal world in which the distribution of outcomes is flatter and the tails are fatter. As such, the mean of the distribution becomes an observation that is very rarely realized"

Richard Clarida's New Normal is analogous to the crisis regime (the dotted line unstable equilibrium in Figures c and d). Any movement in either direction is self-fulfilling and leads to either a much stronger economy or a much weaker economy. So why is the current crisis regime such a long one? As I mentioned earlier, external stabilisation (in this case monetary and fiscal policy) can keep the system from collapsing down to the lower branch normal regime - the "schizophrenia" only indicates that the market may make a decisive break to a stable state sooner rather than later.

Comments

FT Alphaville » Macro-prudence, macro-unintended consequences

[...] links: Securitized Banking and the Run on Repo - NBER Critical Transitions in Markets and Macroeconomic Systems – Macro [...]

Jeremy Stark

you may want to look at the graph of daily 30-day commercial paper rates at: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/cp/ looks to me like a system in equilibrium which shows signs of non-linearity/feedback and then goes totally wild. stick this graph into James Gleick's -Chaos- and nobody would bat an eye....

John

Will the series discuss monetary policy regimes? I'd enjoy seeing your thoughts on Selgin's Less Than Zero argument, which hinges on how well nominal income targeting promotes resilience in the price system. The IEA has the paper in PDF at their site.

admin

Jeremy - Thanks. The magnitude of the catastrophic transition is even even more pronounced in fixed income markets like CP than it is in equities.

admin

John - I hope to take a look at monetary policy regimes but it's a very thorny topic that I haven't made up my mind on fully yet.

The Pathology of Stabilisation in Complex Adaptive Systems at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] stimulus. The phenomenon of ‘rapid cycling’ explains a phenomenon I noted in an earlier post which is the apparently schizophrenic nature of the markets, turning from risk-on to risk-off at [...]