The Control Revolution And Its Discontents

One of the key narratives on this blog is how the Great Moderation and the neo-liberal era has signified the death of truly disruptive innovation in much of the economy. When macroeconomic policy stabilises the macroeconomic system, every economic actor is incentivised to take on more macroeconomic systemic risks and shed idiosyncratic, microeconomic risks. Those that figured out this reality early on and/or had privileged access to the programs used to implement this macroeconomic stability, such as banks and financialised corporates, were the big winners - a process that is largely responsible for the rise in inequality during this period. In such an environment the pace of disruptive product innovation slows but the pace of low-risk process innovation aimed at cost-reduction and improving efficiency flourishes. therefore we get the worst of all worlds - the Great Stagnation combined with widespread technological unemployment.

This narrative naturally begs the question: when was the last time we had a truly disruptive Schumpeterian era of creative destruction. In a previous post looking at the evolution of the post-WW2 developed economic world, I argued that the so-called Golden Age was anything but Schumpeterian - As Alexander Field has argued, much of the economic growth till the 70s was built on the basis of disruptive innovation that occurred in the 1930s. So we may not have been truly Schumpeterian for at least 70 years. But what about the period from at least the mid 19th century till the Great Depression? Even a cursory reading of economic history gives us pause for thought - after all wasn’t a significant part of this period supposed to be the Gilded Age of cartels and monopolies which sounds anything but disruptive.

I am now of the opinion that we have never really had any long periods of constant disruptive innovation - this is not a sign of failure but simply a reality of how complex adaptive systems across domains manage the tension between efficiency,robustness, evolvability and diversity. What we have had is a subverted control revolution where repeated attempts to achieve and hold onto an efficient equilibrium fail. Creative destruction occurs despite our best efforts to stamp it out. In a sense, disruption is an outsider to the essence of the industrial and post-industrial period of the last two centuries, the overriding philosophy of which is automation and algorithmisation aimed at efficiency and control. And much of our current troubles are a function of the fact that we have almost perfected the control project.

The operative word and the source of our problems is “almost”. Too many people look at the transition from the Industrial Revolution to the Algorithmic Revolution as a sea-change in perspective. But in reality, the current wave of reducing everything to a combination of “data & algorithm” and tackling every problem with more data and better algorithms is the logical end-point of the control revolution that started in the 19th century. The difference between Ford and Zara is overrated - Ford was simply the first step in a long process that focused on systematising each element of the industrial process (production,distribution,consumption) but also crucially putting in place a feedback loop between each element. In some sense, Zara simply follows a much more complex and malleable algorithm than Ford did but this algorithm is still one that is fundamentally equilibriating (not disruptive) and focused on introducing order and legibility into a fundamentally opaque environment via a process that reduces human involvement and discretion by replacing intuitive judgements with rules and algorithms. Exploratory/disruptive innovation on the other hand is a disequilibriating force that is created by entrepreneurs and functions outside this feedback/control loop. Both processes are important - the longer period of the gradual shedding of diversity and homogenisation in the name of efficiency as well as the periodic "collapse" that shakes up the system and puts it eventually on the path to a new equilibrium.

Of course, control has been a aim of western civilisation for a lot longer but it was only in the 19th century that the tools of control were good enough for this desire to be implemented in any meaningful sense. And even more crucially, as James Beniger has argued, it was only in the last 150 years that the need for large-scale control arose. And now the tools and technologies in our hands to control and stabilise the economy are more powerful than they’ve ever been, likely too powerful.

If we had perfect information and everything could be algorithmised right now i.e. if the control revolution had been perfected, then the problem disappears. Indeed it is arguable that the need for disruption in the innovation process no longer exists. If we get to a world where radical uncertainty has been eliminated, then the problem of systemic fragility is moot and irrelevant. It is easy to rebut the stabilisation and control project by claiming that we cannot achieve this perfect world.

But even if the techno-utopian project can achieve all that it claims it can, the path matters. We need to make it there in one piece. The current “algorithmic revolution” is best viewed as a continuation of the process through which human beings went from being tool-users to minders and managers of automated systems. The current transition is simply one where the many of these algorithmic and automated systems can essentially run themselves with human beings simply performing the role of supervisors who only need to intervene in extraordinary circumstances. Therefore, it would seem logical that the same process of increased productivity that has occurred during the modern era of automation will continue during the creation of the “vast,automatic and invisible” ‘second economy’. However there are many signs that this may not be the case. What has made things better till now and has been genuine “progress” may make things worse in higher doses and the process of deterioration can be quite dramatic.

The Uncanny Valley on the Path towards "Perfection"

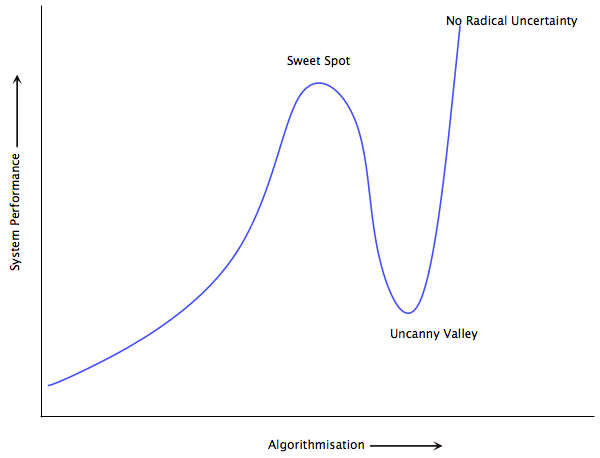

In 1970, Masahiro Mori coined the term ‘uncanny valley’ to denote the phenomenon that “as robots appear more humanlike, our sense of their familiarity increases until we come to a valley”. When robots are almost but not quite human-like, they invoke a feeling of revulsion rather than empathy. As Karl McDorman notes, “Mori cautioned robot designers not to make the second peak their goal — that is, total human likeness — but rather the first peak of humanoid appearance to avoid the risk of their robots falling into the uncanny valley.”

A similar valley exists in the path of increased automation and algorithmisation. Much of the discussion in this section of the post builds upon concepts I explored via a detailed case study in a previous post titled ‘People Make Poor Monitors for Computers’.

The 21st century version of the control project i.e. the algorithmic project consists of two components:

1. More Data - ‘Big Data’.

2. Better and more comprehensive Algorithm.

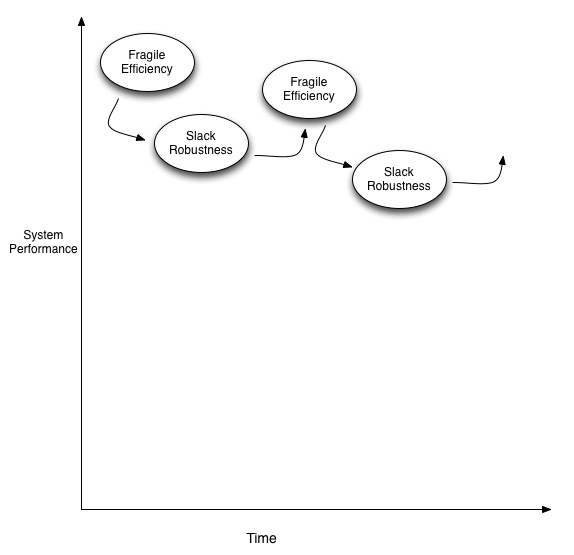

The process goes hand in hand therefore with increased complexity and crucially, poorer and less intuitive feedback for the human operator. This results in increased fragility and a system prone to catastrophic breakdowns. The typical solution chosen is either further algorithmisation i.e. an improved algorithm and more data and if necessary increased slack and redundancy. This solution exacerbates the problem of feedback and temporarily pushes the catastrophic scenario further out to the tail but it does not eliminate it. Behavioural adaptation by human agents to the slack and the “better” algorithm can make a catastrophic event as likely as it was before but with a higher magnitude. But what is even more disturbing is that this cycle of increasing fragility can occur even without any such adaptation. This is the essence of the fallacy of the ‘defence in depth’ philosophy that lies at the core of most fault-tolerant algorithmic designs that I discussed in my earlier post - the increased “safety” of the automated system allows the build up of human errors without any feedback available from deteriorating system performance.

A thumb rule to get around this problem is to use slack only in those domains where failure is catastrophic and to prioritise feedback when failure is not critical and cannot kill you. But in an uncertain environment, this rule is very difficult to manage. How do you really know that a particular disturbance will not kill you? Moreover the loop of automation -> complexity -> redundancy endogenously turns a non-catastrophic event into one with catastrophic consequences.

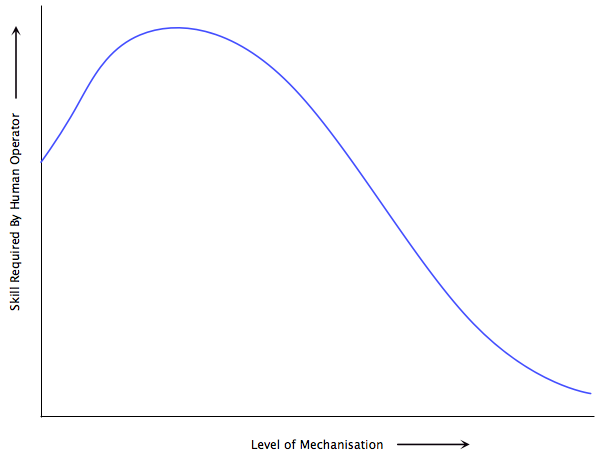

This is a trajectory which is almost impossible to reverse once it has gone beyond a certain threshold without undergoing an interim collapse. The easy short-term fix is always to make a patch to the algorithm, get more data and build in some slack if needed. An orderly rollback is almost impossible due to the deskilling of the human workforce and risk of collapse due to other components in the system having adapted to new reality. Even simply reverting to the old more tool-like system makes things a lot worse because the human operators are no longer experts at using those tools - the process of algorithmisation has deskilled the human operator. Moreover, the endogenous nature of this buildup of complexity eventually makes the system fundamentally illegible to the human operator - a phenomenon that is ironic given that the fundamental aim of the control revolution is to increase legibility.

The Sweet Spot Before the Uncanny Valley: Near-Optimal Yet Resilient

Although it is easy to imagine the characteristics of an inefficient and dramatically sub-optimal system that is robust, complex adaptive systems operate at a near-optimal efficiency that is also resilient. Efficiency is not only important due to the obvious reality that resources are scarce but also because slack at the individual and corporate level is a significant cause of unemployment. Such near-optimal robustness in both natural and economic systems is not achieved with simplistically diverse agent compositions or with significant redundancies or slack at agent level.

Diversity and redundancy carry a cost in terms of reduced efficiency. Precisely due to this reason, real-world economic systems appear to exhibit nowhere near the diversity that would seem to ensure system resilience. Rick Bookstaber noted recently, that capitalist competition if anything seems to lead to a reduction in diversity. As Youngme Moon’s excellent book ‘Different’ lays out, competition in most markets seems to result in less diversity, not more. We may have a choice of 100 brands of toothpaste but most of us would struggle to meaningfully differentiate between them.

Similarly, almost all biological and ecological complex adaptive systems are a lot less diverse and contain less pure redundancy than conventional wisdom would expect. Resilient biological systems tend to preserve degeneracy rather than simple redundancy and resilient ecological systems tend to contain weak links rather than naive ‘law of large numbers’ diversity. The key to achieving resilience with near-optimal configurations is to tackle disturbances and generate novelty/innovation with an an emergent systemic response that reconfigures the system rather than simply a localised response. Degeneracy and weak links are key to such a configuration. The equivalent in economic systems is a constant threat of new firm entry.

The viewpoint which emphasises weak links and degeneracy also implies that it is not the keystone species and the large firms that determine resilience but the presence of smaller players ready to reorganise and pick up the slack when an unexpected event occurs. Such a focus is further complicated by the fact that in a stable environment, the system may become less and less resilient with no visible consequences - weak links may be eliminated, barriers to entry may progressively increase etc with no damage done to system performance in the stable equilibrium phase. Yet this loss of resilience can prove fatal when the environment changes and can leave the system unable to generate novelty/disruptive innovation. This highlights the folly of statements such as ‘what’s good for GM is good for America’. We need to focus not just on the keystone species, but on the fringes of the ecosystem.

THE UNCANNY VALLEY AND THE SWEET SPOT

The Business Cycle in the Uncanny Valley - Deterioration of the Median as well as the Tail

Many commentators have pointed out that the process of automation has coincided with a deskilling of the human workforce. For example, below is a simplified version of the relation between mechanisation and skill required by the human operator that James Bright documented in 1958 (via Harry Braverman’s ‘Labor and Monopoly Capital’). But till now, it has been largely true that although human performance has suffered, the performance of the system has gotten vastly better. If the problem was just a drop in human performance while the system got better, our problem is less acute.

AUTOMATION AND DESKILLING OF THE HUMAN OPERATOR

But what is at stake is a deterioration in system performance - it is not only a matter of being exposed to more catastrophic setbacks. Eventually mean/median system performance deteriorates as more and more pure slack and redundancy needs to be built in at all levels to make up for the irreversibly fragile nature of the system. The business cycle is an oscillation between efficient fragility and robust inefficiency. Over the course of successive cycles, both poles of this oscillation get worse which leads to median/mean system performance falling rapidly at the same time that the tails deteriorate due to the increased illegibility of the automated system to the human operator.

THE UNCANNY VALLEY BUSINESS CYCLE

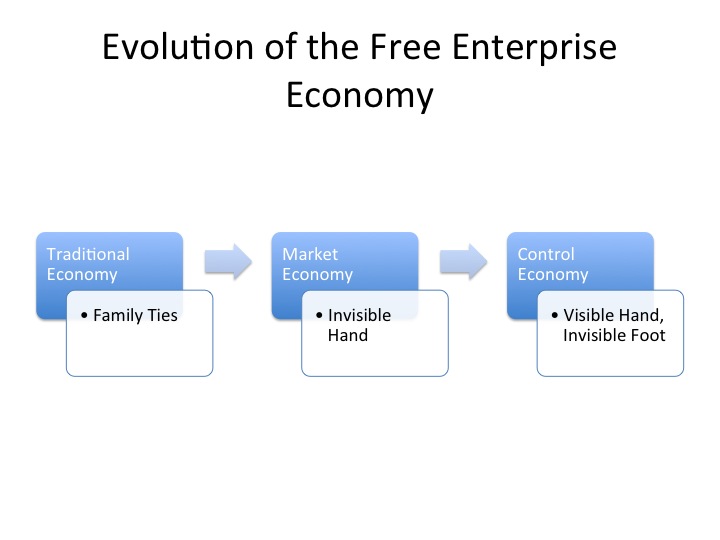

The Visible Hand and the Invisible Foot, Not the Invisible Hand

The conventional economic view of the economy is one of a primarily market-based equilibrium punctuated by occasional shocks. Even the long arc of innovation is viewed as a sort of benign discovery of novelty without any disruptive consequences. The radical disequilibrium view (which I have been guilty of espousing in the past) is one of constant micro-fragility and creative destruction. However, the history of economic evolution in the modern era has been quite different - neither market-based equilibrium nor constant disequilibrium, but a series of off-market attempts to stabilise relations outside the sphere of the market combined with occasional phase transitions that bring about dramatic change. The presence of rents is a constant and the control revolution has for the most part succeeded in preserving the rents of incumbents, barring the occasional spectacular failure. It is these occasional “failures” that have given us results that in some respect resemble those that would have been created by a market over the long run.

As Bruce Wilder puts it (sourced from 1, 2, 3 and mashed up together by me):

The main problem with the standard analysis of the “market economy”, as well as many variants, is that we do not live in a “market economy”. Except for financial markets and a few related commodity markets, markets are rare beasts in the modern economy. The actual economy is dominated by formal, hierarchical, administrative organization and transactions are governed by incomplete contracts, explicit and implied. “Markets” are, at best, metaphors…..

Over half of the American labor force works for organizations employing over 100 people. Actual markets in the American economy are extremely rare and unusual beasts. An economics of markets ought to be regarded as generally useful as a biology of cephalopods, amid the living world of bones and shells. But, somehow the idealized, metaphoric market is substituted as an analytic mask, laid across a vast variety of economic relations and relationships, obscuring every important feature of what actually is…..

The elaborate theory of market price gives us an abstract ideal of allocative efficiency, in the absence of any firm or household behaving strategically (aka perfect competition). In real life, allocative efficiency is far less important than achieving technical efficiency, and, of course, everyone behaves strategically.

In a world of genuine uncertainty and limitations to knowledge, incentives in the distribution of income are tied directly to the distribution of risk. Economic rents are pervasive, but potentially beneficial, in that they provide a means of stable structure, around which investments can be made and production processes managed to achieve technical efficiency.

In the imaginary world of complete information of Econ 101, where markets are the dominant form of economic organizations, and allocative efficiency is the focus of attention, firms are able to maximize their profits, because they know what “maximum” means. They are unconstrained by anything.

In the actual, uncertain world, with limited information and knowledge, only constrained maximization is possible. All firms, instead of being profit-maximizers (not possible in a world of uncertainty), are rent-seekers, responding to instituted constraints: the institutional rules of the game, so to speak. Economic rents are what they have to lose in this game, and protecting those rents, orients their behavior within the institutional constraints…..

In most of our economic interactions, price is not a variable optimally digesting information and resolving conflict, it is a strategic instrument, held fixed as part of a scheme of administrative control and information discovery……The actual, decentralized “market” economy is not coordinated primarily by market prices—it is coordinated by rules. The dominant relationships among actors is not one of market exchange at price, but of contract: implicit or explicit, incomplete and contingent.

James Beniger’s work is the definitive document on how the essence of the ‘control revolution’ has been an attempt to take economic activity out of the sphere of direct influence of the market. But that is not all - the long process of algorithmisation over the last 150 years has also, wherever possible, replaced implicit rules/contracts and principal-agent relationships with explicit processes and rules. Beniger also notes that after a certain point, the increasing complexity of the system is an endogenous phenomenon i.e. further iterations are aimed at controlling the control process itself. As I have illustrated above, after a certain threshold, the increasing complexity, fragility and deterioration in performance becomes a self-fulfilling positive feedback process.

Although our current system bears very little resemblance to the market economy of the textbook, there was a brief period during the transition from the traditional economy to the control economy during the early part of the 19th century when this was the case. 26% of all imports into the United States in 1827 sold in an auction. But the displacement of traditional controls (familial ties) with the invisible hand of market controls was merely a transitional phase, soon to be displaced by the visible hand of the control revolution.

The Soviet Project, Western Capitalism and High Modernity

Communism and Capitalism are both pillars of the high-modernist control project. The signature of modernity is not markets, but technocratic control projects. Capitalism has simply done it in a manner that is more easily and more regularly subverted. It is the occasional failure of the control revolution that is the source of the capitalist economy’s long-run success. Conversely, the failure of the Soviet Project was due to its too successful adherence and implementation of the high-modernist ideal. The significance of the threat from crony capitalism is a function of the fact that by forming a coalition and partnership of the corporate and state control projects, it enables the implementation of the control revolution to be that much more effective.

The Hayekian argument of dispersed knowledge and its importance in seeking equilibrium is not as important as it seems in explaining why the Soviet project failed. As Joseph Berliner has illustrated, the Soviet economy did not fail to reach local equilibria. Where it failed so spectacularly was in extracting itself out of these equilibria. The dispersed knowledge argument is open to the riposte that better implementation of the control revolution will eventually overcome these problems - indeed much of the current techno-utopian version of the control revolution is based on this assumption. It is a weak argument for free enterprise, a much stronger argument for which is the need to maintain a system that retains the ability to reinvent itself and find a new, hitherto unknown trajectory via the destruction of the incumbents combined with the emergence of the new. Where the Soviet experiment failed is that it eliminated the possibility of failure, that Berliner called the ‘invisible foot’. The success of the free enterprise system has been built not upon the positive incentive of the invisible hand but the negative incentive of the invisible foot to counter the visible hand of the control revolution. It is this threat and occasional realisation of failure and disorder that is the key to maintaining system resilience and evolvability.

Notes:

- Borrowing from Beniger, control here simply means “purposive influence towards a predetermined goal”. Similarly, equilibrium in this context is best defined as a state in which economic agents are not forced to change their routines, theories and policies.

- On the uncanny valley, I wrote a similar post on why perfect memory does not lead to perfect human intelligence. Even if a computer benefits from more data and better memory, we may not. And the evidence suggests that the deterioration in human performance is steepest in the zone close to “perfection”.

- An argument similar to my assertion on the misconception of a free enterprise economy as a market economy can be made about the nature of democracy. Rather than as a vehicle that enables the regular expression of the political will of the electorate, democracy may be more accurately thought of as the ability to effect a dramatic change when the incumbent system of plutocratic/technocratic rule diverges too much from popular opinion. As always, stability and prevention of disturbances can cause the eventual collapse to be more catastrophic than it needs to be.

- Although James Beniger’s ‘Control Revolution’ is the definitive reference, Antoine Bousquet’s book ‘The Scientific Way of Warfare’ on the similar revolution in military warfare is equally good. Bousquet’s book highlights the fact that the military is often the pioneer of the key projects of the control revolution and it also highlights just how similar the latest phase of this evolution is to early phases - the common desire for control combined with its constant subversion by reality. Most commentators assume that the threat to the project is external - by constantly evolving guerrilla warfare for example. But the analysis of the uncanny valley suggests that an equally great threat is endogenous - of increasing complexity and illegibility of the control project itself. Bousquet also explains how the control revolution is a child of the modern era and the culmination of the philosophy of the Enlightenment.

- Much of the “innovation” of the control revolution was not technological but institutional - limited liability, macroeconomic stabilisation via central banks etc.

- For more on the role of degeneracy in biological systems and how it enables near-optimal resilience, this paper by James Whitacre and Axel Bender is excellent.

Comments

Michael Strong

Though it is not clear that we have substantive disagreements, your characterization of free market thought (rather than actual institutional history) seems a bit misleading. Are you familiar with Hayek's essay "The Creative Powers of a Free Civilization"? On balance, his analysis strikes me as essentially 100% aligned with yours here and elsewhere. One of the closing paragraphs addresses several of the issues you address above (read in context to get the full meaning, it is the second chapter of his "Constitution of Liberty"): "The competition, on which the process of selection rests, must be understood in the widest sense of the term. It is as much a competition between organized and unorganized groups as a competition among individuals. To think of the process in contrast to cooperation or organization would be to misconceive its nature. The endeavor to achieve specific results by cooperation and organization is as much a part of competition as are individual efforts, and successful group relations also prove their efficiency in competition between groups organized on different principles. The distinction relevant here is not between individual and group action but between arrangements in which alternative ways based on different views and habits may be tried, and on the other hand, arrangements in which one agency has the exclusive rights and the power to coerce others to keep out of the field. It is only when such exclusive rights are granted, on the presumption of superior knowledge of particular individuals or groups, that the process ceases to be experimental and the beliefs that happen to be prevalent at the moment tend to become a main obstacle to the advancement of knowledge." Ultimately Hayek is arguing against large-scale monopolistic regulatory systems on behalf of an evolutionary principle. In combination with public choice theory (the theory of rent-seeking in democratic electoral systems), the implication is that if we want deep, systemic innovation, we need to promote competitive governance. (Hayek thought that there could be credible constitutional barriers to rent-seeking, and designed his own, but in light of the history of constitutional barriers competitive governance seems like a more robust solution). My paper on "Perceptual Salience and the Creative Powers of a Free Civilization" shows the ties between Hayek's argument here and his theory of brain organization, which is also relevant, http://www.flowidealism.org/Downloads/Perceptual-Salience.pdf

Ashwin

Michael - That is an excellent essay! Thanks for the link. Just a few points on where I may be saying something different from you or Hayek. First, the later more institutional Hayek is not really the key influence on mainstream free-market thought. My quibble is really with those who use the dispersed knowledge argument and its utility in achieving equilibrium in 'Use of Knowledge in Society' as the be-all and end-all of free market thought. Obviously your essay and the later Hayek go well beyond that. On the subject of innovation and entrepreneurial discovery, my point pretty much throughout this blog is that the process of the system evolving into the new is often incredibly disruptive and "destructive". And this occasional failure and disorder is the key force in long-run evolution. I didn't use the term because it has too much baggage behind it but this is not dissimilar to the evolutionary concept of punctuated equilibrium. To rephrase it, most of the system relies not on price competition but on a combination of non-price competition, cooperation and occasional dramatic failure. It is the focus on the "invisible foot" of failure that is pretty much absent from conventional thinking and the roots of this order/control/equilibrium approach are very deep in Western civilisation. To take an example, it is not just enough to allow new entrants into the auto industry - you also need to allow GM to fail. Of course it would have been better if failure was allowed in many of these domains a lot earlier in which case the disruption would have been contained.

Smith

Thanks, an interesting read. Just speculatively, I'm wondering whether in this remark: 'Eventually mean/median system performance deteriorates as more and more pure slack and redundancy needs to be built in at all levels to make up for the irreversibly fragile nature of the system.' and your mention of legibility for operators, there isn't a non-orthodox reading of Marx's 'organic composition of capital' to be had. Although he offers an algebraic, formal ratio to describe it, what it actually describes in material, sociotechnical terms strikes me as under-specified (and latterly, has I think been under-explored). What you say about legibility, deskilling and redundancy seems like an interesting way of looking at it.

Ashwin

Smith - Thanks for reading. Marxists have certainly looked at this issue more than most other economists. I haven't read it but Ramin Ramtin's 'Capitalism and Automation' seems to be the go-to reference on this topic. As far as I'm aware, the Marxist reading is how the success of the technical system i.e. the control revolution solves the labour problem of the capitalist and/or leads to the end of capitalism - they essentially assume that full automation will happen soon. Whereas I'm looking at the potential failure of the technical system close to "perfection" - what it means for the socioeconomic system, class struggle etc apart from fragility and underperformance, I haven't really thought about.

Diego Espinosa

Ashwin, Excellent essay. I disagree with strategic thinking dominating at the firm level, though. Firms would rather engage in control projects with known payoffs than in risky allocation decisions. I say this as a former strategy consultant that saw very little true strategy work being done during my tenure at a top firm. Most of the work had migrated to (extremely boring) process efficiency projects. The above supports your thesis. Not only is the "foot" missing, but oligopolistic competition is incredibly stable as large firms do not seek to de-stabilize their own industries in search of positional advantage (involving large and risky investments). Apple is the exception: the truly disruptive large firm. Jobs regularly bet the farm; most CEO's would rather hang on to their legacy rents and improve efficiency. Hence, our high corporate profits-to-GDP ratio is partly a function of managers agreeing not to think strategically.

Ashwin

Diego - I agree with everything you've said so I'm not sure what we're disagreeing about. I expanded upon a similar argument on incumbent incentives in an earlier post https://www.macroresilience.com/2010/11/24/the-cause-and-impact-of-crony-capitalism-the-great-stagnation-and-the-great-recession/ . On this topic, my thinking is almost completely synonymous with that of an incredibly under-read economist Burton Klein. To quote from his book 'Prices, Wages and Business Cycles': "the degree of risk taking is determined by the robustness of dynamic competition, which mainly depends on the rate of entry of new firms. If entry into an industry is fairly steady, the game is likely to have the flavour of a highly competitive sport. When some firms in an industry concentrate on making significant advances that will bear fruit within several years, others must be concerned with making their long-run profits as large as possible, if they hope to survive. But after entry has been closed for a number of years, a tightly organised oligopoly will probably emerge in which firms will endeavour to make their environments highly predictable in order to make their environments highly predictable in order to make their short-run profits as large as possible." If you can find them, both his books 'Dynamic Economics' and 'Prices, Wages and Business Cycles' are highly recommended. The fact that we have a corporate savings glut and not a household savings glut tells us that this is the problem.

isomorphismes

What is your basis for calling ours The Algorithmic Era? other than a few news stories of course.

Ashwin

Algorithmic Revolution is my terminology for what James Beniger has called the Control Revolution. His book is the best reference on why this term is a fair description for the last 150 years.

Caffeine Links 3-14-2012 | Modern Monetary Realism

[...] The Control Revolution And Its Discontents at Macroeconomic Resilience [...]

LiminalHack

Ashwin, What do you know about entropy maximisation (a.k.a maxEnt)? It applies to complex systems, and I think to the economy. It also relates to resilience.

blavag

Fascinating and well done. Many useful references too. You might want to expand the connection to the socialist calculation debates of the 1920s and 30s that led to much of the "data and algorithm" approach in economics and the social sciences. I strongly recommend Philip Mirowski's brilliant Machine Dreams. Also important is S.M. Amadae's Rationalizing Liberal Capitalism and of course David F Noble's study of industrial automation, Forces of Production. A point that I would stress is that the control revolution is less a project of "modernity" nor a technical response to general problems so much as a specifically political, power based, development under particular conditions.

Ashwin

LH - short answer is not much. blavag - Thanks. Thanks for the references - I will definitely look them up. Am familiar with the socialist calculation debates - my only point is that the Hayek-Mises point is more about how the right equilibrium is attained whereas I think (drawing on Joseph Berliner) that it is the inability to get out of equilibria that crippled the Soviet project. My thoughts on the origins of the control revolution are still a work-in-progress but my current bias is that there are deeper origins to this than just a power project.

Brian Balke

Ashwin: A key figure in the early years of computer system design related to me that software is principally the means of disseminating the decision-making skills of the expert to people that form relationships and collect information. The challenge, of course, is that engineering success makes human intention the most important subject for control. The critical adaptation for most people is therefore influence over those around them. This creates conditions under which human behavior evolves very rapidly, which undermines the effectiveness of control algorithms. Witness, i.e., the growing religiousity of American society - or the "bread and circuses" culture of celebrity. This leads to an interpretation of the modern "Economy" as a set of conventions for distributing resources to sustain political activity. According to "The Post-Carbon Reader", this is contingent upon efficiencies in the energy and food production sectors that may not be sustainable in the face of Peak Oil and Global Climate Change. So maybe there's hope for the "foot" after all!(?) Not that I would wish it upon anybody.

Brian Balke

I should have said: "The critical adaptation for most people is therefore the development of behaviors that provide influence over those around them."

blavag

Ashwin, Pedantically, but with admiration, let me also bring to your attention the following: Francis Spufford, Red Plenty on the Soviet industrialization debates, Philip Mirowski, More Heat than Light on the use of energetics metaphors in economics, Steve J. Heims, John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener: From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death on the origins and different paths taken in cybernetics, and Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow on the uses of stochastic oscillation and feedback among other things. On the Soviet economy, if you have access to a university library or JSTOR see also: WHITSELL, Robert S Whitsell, "Why Does the Soviet Economy Appear To Be Allocatively Efficient?" Soviet Studies, vol 42, no.2 April 1990 On the social background of the Hayek/Mises/Friedman axis as the fighting ideology of reaction see : Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, The Road from Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Recall that Hayek particularly but also Popper and von Neumann were heavily traumatized by the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and then Red Vienna and then the Nazis. One must be careful of a Platonic economics as social physics. Many technically trained people especially engineers tend to gravitate to economics because of its similarities to linear programming and so optimization and systems analysis and what used to be called "computer programming" as well as basic mechanics in which price and utility take the place of kinetic and potential energy respectively. This is a danger: the concept of energy used in economics unwittingly or not is mid 19th C and predates thermo, Shannon's entropy is not the same as thermo entropy, and utility cannot be operationalized or even adequately specified. Nor is equilibrium as used in general or partial equilibrium theories the same as that in physics. Any similarities are metaphorical rather than actual. Nor are the formalisms of economics based on generalization of empirical evidence but are rather external and imposed on inchoate data either naively or for political reasons. Looking forward to more of your work.

Ashwin

Brian - Thanks for the comments. blavag - Thanks! More for my ever-expanding reading list and my occasional trips to the British Library! The Whitsell paper seems to be especially relevant.

Carolina

Ashwin - you brought up several interesting points. I was particularly intrigued by you concept of deskilling. As an engineer, I see evidence of that all the time. Also, would you consider the demise of the "Soviet Project" to be creative destruction?

Ashwin

Carolina - Thanks. On the Soviet project, it is more akin to systemic collapse than creative destruction. which is the risk when the system is stabilised and controlled for too long - the creation that accompanies low-level "destruction" disappears when the magnitude of the destructive event increases beyond a point.

Legibility, Control and Equilibrium in Economics

[...] argument sees the illegibility and uncertainty as justification to put in place a system of control whereas the invisible-hand argument claims that the system is legible and at [...]

Metatone

Coming to this incredibly late, I feel compelled to suggest that there is an alternative way to look at the evidence. Fundamentally, the Schumpterian concept is an abstraction and doesn't actually map on to reality. "Creative destruction" is an occasionally useful analytical shorthand, but it doesn't actually represent how innovation, particularly disruptive innovation occurs. Key points to consider: 1) When you undertake micro examination of actual innovations Creation and Destruction tend to be separated in time by quite a distance. 2) Fundamentally less destruction/creation occurs than Schumpeter suggests. Restructuring is far more common a mode of change. There's a repeated mistake in asserting (as Chris Dillow does) that productivity improvements come from market entry/exit. This is not in the majority the case historically in the US/UK, esp. for disruptive innovations and is not the case at this time in places like Korea and Germany. This is not to say that CD doesn't exist or doesn't happen or isn't needed sometimes - but it's the minority, the corner case. The real history of innovation is that disruptions most often work through and change existing institutions, very often including companies or sectors...